The Child Psychiatrist is In Your Living Room

Posted in: Hot Topics

Topics: Anxiety, Behavioral Issues, Depression, Mental Illness + Psychiatric Disorders

Telepsychiatry is much like the old days of visiting patients in their homes.

For a child and adolescent psychiatrist, home visits – and now telehealth visits – allow us to see our patients’ treasured stuffed animals, games, posters, sports team banners – even their piles of dirty sweatshirts and sneakers. Since the pandemic, therapy is now mostly home-based. And whether we meet with the just the child or teen, or the whole family, there is a kind of intimacy, despite the seeming coldness of the screen. Actually, for most of us, the coldness warms with the regularity of our sessions.

In early 2020, seeing a psychiatrist or therapist via telehealth was still a novelty. Although the technology had been around in various forms for decades, most mental health providers prior to COVID worked in brick-and-mortar buildings. Telehealth was mostly used as a way to reach underserved communities with limited, physical access to healthcare providers, such as residents of small rural towns or members of Native American tribes. This was just as true for children and adolescents as it was for adults and families.

When COVID arrived, it caused a major crisis for healthcare delivery. While many doctors struggled to see patients safely face-to-face, mental health visits were ideally suited for telehealth due to a limited need for physical exams. The primary barriers were on the payment and the regulatory side.

In March 2020, the national Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) temporarily suspended several requirements, and states and insurers followed suit. This allowed psychiatrists to receive the same payment for a video or phone visit as they would for an in-person visit, and to offer care without putting the patient or provider at risk of COVID. In a single month, psychiatrists, therapists and other mental health providers flipped their practices from nearly 100% in-person to nearly 100% telehealth.

Reba Benschoter, PhD, a telehealth pioneer in Nebraska in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

As the chair of the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) Department of Psychiatry and a child and adolescent psychiatrist, I experienced this transition firsthand. Nebraska is a state where telehealth was first pioneered over 50 years ago, so there were already some telehealth experts on faculty. However, in our department, 95% of our mental health visits were still in-person as of March 2020.

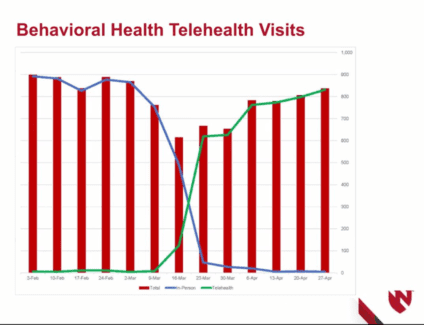

As COVID began to spread statewide in March, dozens of mental health professionals scrambled to convert their patients to telehealth visits (see Figure below). In my clinic, I found that most parents, teens, and children took the changes in stride. Suddenly, we were meeting in a bedroom where a goalie would proudly tell me about her trophy before sharing the stress of cancelled athletic events. Or it might allow me to ask a kindergartener about bullying while he sat on his living room couch with a new puppy clasped in his arms. These home telehealth visits created small moments which told me so much about families. Telehealth opened my eyes to the value and the privilege of a house call to meet our patients in their natural states.

During the first month of the pandemic, the total number of visits stayed consistent in the Nebraska Medical Center Psychiatry Clinic and the number of telehealth visits far outweighed the face to face visits. (Key: green line = telehealth visits, blue line = live visits, red bars = total visits

When COVID ends, we must preserve telehealth as a point of access for kids and teens. It is critical for rural families to avoid long commutes to see a child psychiatrist, and it is equally helpful for urban parents who dread the prospect of bored siblings in a waiting room. Before COVID, patients routinely missed appointments when their car failed, or a sibling was sick. Now, those visits still happen as long as the technology is working, and if it fails, we can convert to a phone visit. Our clinic found that patient satisfaction improved dramatically when we switched to telehealth visits.

Of course, telehealth is not ideal for all patients or families. Kids with poor attention spans often wander off screen, and people with hearing or visual disabilities may have more challenges communicating. And the mental health provider, too, might miss a subtle nonverbal cue that they might have seen in the office. But in 2020, telehealth is “good enough” to get the job done for most families.

Still, telehealth does not fix every gap in care. The families that struggle the most to access telehealth are the ones who face other life challenges: a single parent whose phone is broken, a rural family with poor WiFi or other internet barriers. After COVID-19, we must continue to offer patients both in-person and telehealth options, and to work with community leaders to address poverty, unstable housing, unemployment, and the fact that one in three rural Nebraskans lack high speed internet access.

Elected officials have a key role in supporting equal payment for telehealth services at the federal and state level and the ongoing suspension of restrictions to practice across state lines. Access to life saving mental health treatment should not depend on where we live or on restrictive insurance practices. A mental health visit in the office is comparable to a mental health visit online. And the benefit of continuity of care far outweighs any minor downside to an office visit.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet