Navigating Special Education in Schools Part 1: Legal and Practical Tips

Posted in: Multimedia, Parenting Concerns, Podcast

Topics: Learning + Attention Issues, Mental Illness + Psychiatric Disorders

This is the first blog post in a two-part series on navigating special education in schools. The focus of this first post is on general legal and practical tips for parents. The second post focuses on working with the IEP and your child.

Welcome back to a new season of Shrinking it Down: Mental Health Made Simple!

For our season premiere, Gene and Khadijah are joined by two special guests who specialize in learning disabilities and special education law – Ellen Braaten, PhD, and Eileen Hagerty, Esq, – to do a deep dive on the special education system. On part 1 of this two-part series, they provide legal and practical tips by discussing the definitions, rights, and processes involved in special education evaluations

- Learning & Emotional Assessment Program (LEAP) (MGH)

- Ellen Braaten, PhD (MGH)

- Eileen M. Hagerty, Kotin, Crabtree & Strong, LLP (KCS Legal)

- Massachusetts Advocates for Children (Mass Advocates)

- Coping With ADHD: How A Young Man And His Mom Are Managing The Path To Success (MGH Clay Center)

- Our Greatest Strengths, Part 2 (Shrinking it Down)

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (US Department of Education)

- Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) (US Department of Education)

- Intro to Processing Speed (MGH Clay Center)

- What are the Best Treatments for ADHD (MGH Clay Center)

- Dyslexia 101 (MGH Clay Center)

- What is Autism (MGH Clay Center)

- Massachusetts Advocates for Children Helpline (Mass Advocates)

Episode Transcript

SPEAKERS: Gene Beresin, MD, MA; Khadijah Booth Watkins, MD, MPH; Ellen Braaten, PhD; Eileen Hagerty, Esp.

[INTRO MUSIC BEGINS]

Ellen Braaten 00:00

There is not a week that goes by that I do not hear or supervise a case where a parent said, I wish I had done this sooner. It’s almost always the case, but there’s still a lot of parental stigmas about their child being labeled, tracked in some way that’s not to their benefit, and that’s why all of these laws are in place to try and prevent that, but it is. It’s a scary process for any parent.

[INTRO MUSIC ENDS]

Gene 00:29

Welcome back to a new season of Shrinking it Down: Mental Health Made Simple. I’m Gene Beresin

Khadijah 00:34

and I’m Khadijah Booth Watkins,

Gene 00:36

And we’re two child and adolescent psychiatrists at the Clay Center for Young, Healthy Minds at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Today, we’re going to be doing a deep dive into the special education system, and to help us make sense of this complicated system, we’re delighted to have two special guests who specialize in learning disabilities and special education law. I’d like to welcome Dr Ellen Braaten who, by the way, was a former Associate Director at the Clay Center, so she’s our professor emeritus, and Eileen Hagerty, who’s been doing legal work in this area for many years.

Ellen Braaten 01:15

I can say it’s great to be back here. I’ve missed you both and miss the Clay Center. So, it’s wonderful to have this chance to talk with both of you, especially in your season opener. So, it’s a great, great, great topic. And also to be here with Eileen too, who I’ve worked with for decades on cases. So, it’s a, really a homecoming for me a little

Eileen Hagerty 01:40

And this is Eileen. I’m so glad to be here, too, with Ellen and with Gene. And you Khadijah.

Gene 01:47

So, you know, one of the reasons we’re doing this is because, as a child adolescent psychiatrist for 40 years or so, and Khadijah, I you as well. I’m sure, just a few,

Khadijah 02:02

A few years less, a few years

Gene 02:03

Less. But, you know, it’s not uncommon that, as a parent or a caregiver or a teacher or somebody will say, you know, I think my kids having a problem. They’re not they’re not succeeding, they’re not doing well in school. They need something. They need some kind of an assessment, and unfortunately, and it’s probably, it’s probably because the schools are so overwhelmed that they just don’t have the bandwidth to kind of help explain what the mechanisms are to kind of help your kid out. So that’s one of the reasons why we wanted to make this a season opener. So let me introduce Ellen. Ellen Braaten is executive director of the Learning and Emotional Assessment Program, LEAP program at Mass General Hospital. She’s track director of the Child Psychology Training Program at the MGH Harvard Medical School, and former co-director at the Clay Center. Dr. Braaten is widely recognized as an expert in child, adolescent and young adult psychological assessment, particularly in areas of assessing living disabilities and disorders. So it’s great to welcome you back to the podcast, Ellen. It’s been a few years.

Ellen Braaten 03:14

Yeah, it’s really great to be here,

Khadijah 03:19

And so I have the pleasure of introducing Eileen Hagerty Esquire, who’s a Partner at Koton, Crabtree and Strong in Newton, Massachusetts, and has concentrated her practice on special education law since 1998 prior to joining the firm, she served as a partner in a boutique litigation firm as the Assistant United States Attorney and a Special Assistance District Attorney, Eileen lectures and writes frequently on topics in special education law for both legal and lay audiences. She participates in various public service activities, including serving as chair on the board of directors for the Massachusetts Advocates for Children. Welcome Eileen, and we are thrilled to have you join us today for this very special season opener. We think it’s super timely, because, again, like Gene said, this is an area where people are often confused, and they need some guidance and direction. So, thank you for joining us.

Eileen Hagerty 04:09

I am so glad to be here. Thank you, Khadijah,

Khadijah 04:12

So, Ellen and Eileen, before we get into our discussion, is there anything else you think our listeners would like to know about you, your background, how you got into this field or this area of specific interest for you, do you think anything of interest

Ellen Braaten 04:25

I could, I can add a little bit of something I got interested in this whole field because I was originally a special education major and a special education teacher right out of undergrad, and became a psychologist after I had taught special education for a while, and so this is sort of like the heart of what I love doing, because it’s what I started doing. And I should say, too, that I became interested in special education because they have a brother with Down Syndrome. And in fact, I think he was on the podcast very, very long time ago. And I just. It was that he’s now around 50 years old, and I he was one of the first kids to go through special education in this, in this, the laws that we’re talking about today really started about 50 years ago or so. So he was sort of a pioneer. My mom was kind of a pioneer of having to get support for him using the laws that were just being developed. So, I was sort of raised, even when I was in, you know, middle school and high school, I would go with my mom to her team meetings, which weren’t something that everybody knew about then. And so it’s part of my, my DNA, in a way, this sort of special ed law, and the, you know, these sorts of rights are, you know, basic rights that we’re not always there so for different kinds of learners and kids. So, I think it’s an important issue to cover.

Gene 05:55

And I might add that we have in the past if, if listeners want to take a look at our video podcasts. You brought your son to two video podcasts to talk about his learning challenges, and at that time, he was seeing Steve Schlozman, yes, his care. And so, we had his, we had his psychiatrist, his mom and me.

Ellen Braaten 06:22

Right? So, I’ve been on all sides of this as a as a young sister, as a mother, as a professional and it’s hard to navigate all of this, and I still learn every month, every year, new things about this, and it’s always changing too. So yeah, yeah.

Eileen Hagerty 06:44

I think it’s not uncommon for people in this field, whether it’s lawyers, evaluators, teachers, to have a personal connection. And in my case, my husband and I have three children, one of whom has significant autism, and when he was three, which is the age at which you start moving from early intervention to talking to your school district about special ed, we had to fight the town where we were then living about his education to get him the services he needed. And indirectly, I was already a lawyer, already doing civil litigation, but indirectly, that’s what got me into special ed advice and litigation

Gene 07:19

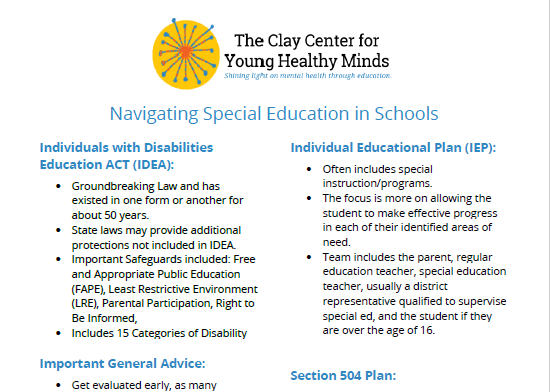

So interesting. So, so let’s get into the education, special education system, and maybe we can start with some basic definitions. So, the main legislation we’re going to discuss is the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or IDEA. So, Eileen, what exactly is IDEA? And how does it, what does it guarantee at a federal level and for the states?

Eileen Hagerty 07:48

Well, IDEA, as Ellen mentioned, has been around in one form or another, not always under that name, for about 50 years. It was a groundbreaking law at the time. It’s actually a federal funding, so it doesn’t guarantee freestanding educational rights. It’s all tied to the states accepting, if the states accept federal special education funding, they must agree to certain safeguards for students, and perhaps the most basic one of those safeguards, or those principles, is the right to a free, appropriate public education, often called FAPE. F.A.P.E the acronym, for eligible students with disabilities. So, if a state accepts federal funding, it must for special ed, it must agree to provide FAPE to eligible students in the district. Another important principle in IDEA is that of the least restrictive environment, often called LRE for short, and that’s the principle that if a student can be successfully educated in an environment with non-disabled students, he or she should be to the extent possible. That doesn’t mean that in every single case, that’s going to happen, because of course, there’ll be some students who can’t, whose needs cannot be met in an integrated setting, but that setting is preferred if it if it’s educationally appropriate. So, another basic concept is that a parental participation. I know we’ll be talking about that, but the right of parents of students with disabilities to be informed and to participate in the process, and I should mention also, state laws may provide more protection than IDEA. So, IDEA operates, as the courts have said, operates as a basic floor of rights. So, if the state accepts federal funding for education special ed, it must guarantee the rights that are in IDEA, but states are free to provide more rights, and in some cases, they do so. It’s always a good idea for anybody who’s got a question about special ed law to look not only at IDEA, but at their state’s law as well.

Gene 09:57

Now one thing that frequently comes up, and maybe you could help us understand this is that the special education services we always we think about them largely in terms of learning challenges or learning disabilities, but they also involve emotional or behavioral problems. Is that right?

Eileen Hagerty 10:15

That’s, that’s correct. So federal law has 15 categories of disability, and one of those is called emotional disturbance. I’m not sure I like that term, but that’s the term they use in the federal regs. But that means that students who have mental health issues, for instance, emotional issues, behavioral issues, perhaps if those problems interfere with their education, if they require specialized services to address those problems so they can get an education, then they may be eligible for a special ed or for a Section 504 Plan. I know we’re going to 504 in a bit. So, it’s not just a matter of fitting into one of these categories. However, the student would have to be eligible for special ed. Under IDEA, would have to fall into one of the categories, but then would also have to the team would have to agree, or the parents would have to show that the student needs special education. Or in some states, only related services would be enough to qualify you, and they have to need it because of their disability, there has to be a causal connection between the students, let’s say emotional problems, and their failure to do well in school, such that they need specialized instruction or so called related services.

Gene 11:35

And one, one final question of definitions, and that is, what’s the difference between an IEP individual, an Individualized Educational Plan, and a 504 because we often throw those terms around. And I think many parents would want to know what the differences are?

Eileen Hagerty 11:53

Yes, that’s a good question. And you we could spend the rest of this hour, which I promise I won’t do, but if, if you think about it, I mean, they both. So Section 504, of the Rehabilitation Act is the section we’re referring to, and it came out of the same impulses in the 60s and 70s as IDEA did the impulse to include people with disabilities, children with disabilities in all aspects of society, including education. So, but 504 and IDEA are quite different in their emphasis, their approach, their philosophy. The principle behind 504 is to guarantee children with disabilities. Well, 504 applies to a whole range of issues, employment, housing, whatever, but if we’re looking only at education, it’s to its purpose is to provide the student with disabilities with a level playing field so they have the same access to services that their nondisabled peers do. Under IDEA, by contrast, the principle of behind FAPE is that the free appropriate public education is that the student will make effective progress relative, not so much to his or her peers, but relative to his or her own disability, that the services will allow the student to progress. So one concept is about access, 504, and one’s more about progress, IDEA. Of course, they sort of overlap, because every student on an IEP, it’s sort of like a Venn diagram that students in IEP are the smaller circle within the bigger circle, that’s 504 so any student on an IEP is protected by 504 but the reverse is not at all true, and I probably it probably doesn’t make sense to get into a long list of differences right now, but there are, in general, 504 is a much, much sketchier, terser, less detailed statute, less well fleshed out. There are fewer procedural rights than under IDEA for parents and students. There’s a lot less specificity about how 504 teams are to do their work, as opposed to IDEA being quite specific about IEP teams, so that the two statutes are quite different.

Khadijah 14:10

So, if we could take a step back, so how do we know if a child is struggling, and is it the parent’s responsibility or the school’s responsibility to identify these kids who might benefit from either an IEP or 504

Ellen Braaten 14:23

I can talk about the evaluation process, at least, like that gut feeling that a parent has when there’s something going on, and probably we’ve all been there at one point or another in this conversation, or know someone who has. And it’s not really that clear cut in terms of how this starts, who starts the process now, Eileen will talk about the legal kinds of issues, but it usually starts with a parent wondering, is something not quite right? And that’s where it gets already, from the beginning can be very murky for a parent, because how do you know that? Is it, you know, is it that they’re just not reading at a certain level, or is it that the teacher is saying they’re not behaving, or they’re not attending well enough? It’s usually very it’s not very specific. So it starts with a with either a teacher saying there’s something not going on, or a parent feeling like, I don’t think my child is doing as well as they should be doing, and so that’s where, then when, when the idea of an evaluation comes up, that’s when it sort of like kicks into a legal kind of issue. So sometimes it’s the teacher saying, I think this child needs to be evaluated, and sometimes it’s the parent saying it, and sometimes it’s neither the teacher nor the parent, but a pediatrician or psychiatrist or somebody so it it’s a little bit complicated, even from the beginning, and that’s where I guess I’ll turn over to you, Eileen, to say, like, Where does where then are the legal parameters for this?

Eileen Hagerty 15:59

Thanks. Ellen. Well, I should start by saying school districts under IDEA have a so-called Child Find Obligation, meaning they are supposed to locate children within the district who are in need of or who may be in need of special ed services and refer those students for evaluation. IDEA says that referrals can be made by parents or by a state agency, a school district or other agency. Some states have broader laws. I know in Massachusetts, anybody in a caregiving position can refer for evaluation, which although, as Ellen says, sometimes that suggestion comes from the treating doctor, let’s say to the parents, but in any event, so in my experience, more often the parents are the ones requesting the evaluation. And I’ve heard many tales of a teacher taking the parents aside and saying, you didn’t hear it from me, but you should request an evaluation. But you know, whoever it comes from, the process is the same. Once the district receives the evaluation request, they send out a proposed consent to the evaluations, specifying what evaluations they intend to do, and then once they receive written consent back from the parents, a timeline starts running for the district to do its evaluation. What is that timeline? It can vary state to state. IDEA says 60 days, 60 calendar days from receipt of the consent, unless the state has a different timeline. I would interpret that to mean the state’s timeline would have to be shorter than 60 days under that principle that states cannot take away rights under IDEA, but in any event, that 60 days should be the outside for the timeline. And I, I would echo what Ellen said about parents trusting their gut. Again, I’ve had a lot of parents say to me later on, when a student is say in fourth, fifth, sixth, eighth grade, high school, that they wish this would be like students with learning disabilities, dyslexia and so on. I’ve had a lot of parents say to me they really wish that they had trusted their instincts when the student was in kindergarten or first grade and had had the evaluation then, and instead, they sometimes allowed themselves to be lulled by a teacher saying, Oh, he’s just taking a little more time. Oh, boys are slower. And of course, as parents, that’s what you want to believe. Nothing’s wrong. It’s just taking a little more time. But there’s no harm in getting the evaluation and finding out. So that’s that would be my advice, if parents suspect that something is wrong, there’s no downside to getting an evaluation, except the time involved. The evaluation is to be free. The one done by the school district is to be free to the parents. They can get a private evaluation at their own expense if they want to. And in some circumstances, there’s a right to a publicly funded independent evaluation, which we can get into later if we want to. But, you know, my advice would be, get the information.

Ellen Braaten 19:18

I mean, I just have to second that too. Yeah, because I have never in my life had a parent say, I wish we hadn’t done this so soon. But there is not a week that goes by that I do not hear or supervise a case where a parent said, I wish I had done this sooner. It’s almost always the case, but there’s still a lot of parental stigmas about their child being labeled, tracked in some way that’s not to their benefit, and this is why all of these laws are in place to try and prevent that. But it is. It’s a scary process for any parent and but the sooner, the better. I’ve never again. I’ve never had anybody regret saying we did this too soon. This is too much information, too soon.

Khadijah 20:07

So, and we often say here, you know, the parents are the experts on their kid, and so how? How do they, once they get that gut feeling that something is not right or progressing in the manner it should be? What? What is the how do they actually request an evaluation? Is there a process that has to happen?

Eileen Hagerty 20:24

Well, interestingly, IDEA doesn’t require that the request be in writing, but I would always advise parents to put the request in writing so that they can prove that they made it and when they made it. And I would advise them to summarize just in a couple of paragraphs, what you know, who their student is, what the issues are, why they think the student might need an event, might have special needs, might need an evaluation, and then they’ll be in and so the district ought to take that and propose an evaluation, and then there, there is supposed to Be options, opportunities for parental input during that process.

Gene 21:04

So, Ellen, What? What? Let’s say the parent asks, and they referred to you, whether it’s through MGH or privately, or whatever, or, or they do it through schools. What goes into building an IEP or a 504, what kinds of tests? What? What are the general? What are the general? What are the general ways that you as a psychologist would want to see a child evaluated?

Ellen Braaten 21:36

So I think it’s a little bit different whether it’s private, and I think I know it’s different whether it’s a private evaluation or school evaluation, and part of that has to do with the purpose of the evaluation, which is in a private evaluation, the psychologist wants to hear the referral question. They want to answer the question so it could be, does my child have trouble paying attention? Is my child struggling with reading? And does that difficulty meet criteria for a disability, and that label that will assign to the child gives us a sort of guiding north star as to where we need to go. What are the kinds of treatments we know, the sorts of treatments that are good for ADHD, for dyslexia, for dysgraphia, which is a disorder of written expression and on and on, that label helps us figure out what is the best treatments that we need in school, they’re trying to really determine, and this, this is why it gets into the tests that are picked in school. They’re trying to determine how to best meet that child’s needs within the school system so that they can function, and Eileen will have the right labels for this, but so that they can function at a level that they are, you know, that is appropriate for their ability level. And so, the tests that are used in the school evaluation, they’ll look at those issues that are problematic within the classroom setting. They don’t typically look at issues that are problematic outside of that. So, for example, if a child is exhibiting symptoms of depression at home and in every area other than school, they’re not going to look for that and so and they’re also not going to develop a treatment plan around that in a private evaluation. What I want to do is, I want to look at the total child, even if it’s not an area of issue. I want to look at the areas of strength too. I want to see, you know, what is this childlike as a learner, as a thinker, in terms of their behavioral issues and also emotional functioning, the pros and cons, the positives and negatives. In school, they’re not necessarily looking at that, so the test batteries that are constructed are sort of constructed using that, typically in outside evaluation will be much more comprehensive, and a school evaluation may actually sometimes be more comprehensive, but oftentimes it just focuses on the areas that they really want to specifically look at so if it’s reading, they may just look at reading. If it’s math, they may just look at math, or they may just look at behavior and not look at reading at all, because the teachers think it might be a behavior problem or an intentional issue.

Gene 24:14

Well, is it important for a parent to have a checklist? For example, if they go to, if they go to a school psychologist, let’s say, oftentimes. And this gets, this gets into tax base and available funding, because the poorer school districts tend to have, you know, a greater, I mean, it could all of this stuff costs money, right? I mean, so they have to be able to pay for the evaluations. And what I’ve seen is in in areas where they’re overwhelmed with issues and problems, they may only do academic testing. They may not do other kinds of testing. So the parents, if they’re worried about emotional. Problems, or behavioral problems, or certain specific learning problems like paying attention or distractibility. Should they have? Should we? Should we be able to provide them a checklist, which we could add to this podcast if we wanted to about what they should actually ask of this special ed director at the school that they would like to see done.

Ellen Braaten 25:26

I think that’s a great idea. I think that there’s still a lot of difficulties. It’s a fabulous idea, but parents still don’t know. They don’t have the knowledge, nor should they have the knowledge. This is not part of their job, to know whether or not their behavior, their concerns, were adequately evaluated. And that’s where it gets really tricky, and especially in parents who don’t have that experience. And we’re really talking about parents being fairly sophisticated at knowing it’s, you know, this sort of an issue, and I need this sort of a test, and this is the person who is best equipped to evaluate that child. So it’s, it’s a starting point, but it’s, it’s still pretty tough for parents to know that, which is why I might suggest too, like getting a professional involved, even just a pediatrician, I don’t mean to say even a pediatrician, but, but a pediatric, everybody has a pediatrician to be able to say, Does this seem right to you? Does this? Did they? Are they looking at this enough? And so I don’t know. Eileen, do you have any ideas about that?

Eileen Hagerty 26:36

Yeah, well, parents should try to request evaluations in every area of suspected special needs, the district only might well, in my experience, here in Massachusetts, most districts and initial evaluation if, if it’s a suspected learning disability, would do a psychological and an academic evaluation, usually by in house people. But you know, if the student has communication issues, maybe one of parents want to request a speech language evaluation or coordination issues, if you want to request an occupational therapy, physical therapy evaluation, that kind of thing. And it’s important to remember, too, that this is not their one and only shot at an evaluation. If the initial round of evaluations raises questions about other potential areas of need, the parents or the district can always propose the more evaluations after that. And I would agree with Ellen about the independent evaluations, the privately obtained evaluations, often being more complete, more thorough, more clear, containing, more direct diagnoses and more direct recommendations often than school district evaluations. And so, for parents who can afford independent evaluations themselves, they might even want to do that before they request the school district evaluation.

Gene 27:56

And are they? Are they covered by insurance? Depends right on it, because it’s a big question that they always ask me, and I always say they have to have a cognitive deficit or a problem with their brain functioning in order for insurance to pay for it. That’s in general, but it what do you? What do you? What do you think Ellen?

Ellen Braaten 28:18

In general, what I find is that parents who push very hard for their insurance companies to pay for the evaluation generally get it paid for, with the exception of if it’s just academic, they don’t. So, if, if your child is just struggling and reading, and that’s not a just again, I’m not. I don’t like using this term because if you’re struggling reading, you’re really struggling in school, but that insurance companies don’t tend to cover that. They do tend to cover out to cover rule outs for Autism spectrum, sometimes ADHD, especially if you can make a case that you’re trying to figure out medication versus non, and you can sort of make a case for insurance to cover it if there’s any sort of issue related to birth, trauma, premature birth. I mean, we can be pretty broad on this, but what I find is that parents who are persistent generally get something covered. The other issue too is that in Massachusetts, if you are under sort of any of the subsidized insurance plans that generally is covered, believe it or not, they have better coverage than some of like the Blue Cross plan. I shouldn’t mention these by names, but then some of the other plans. The problem, though, is that to get an appointment for that kind of evaluation is probably going to take you 12 to 18 months. So while it’s covered by the state plans, you’re going to have a lot of trouble finding somebody who has availability for that. So, it’s really complicated. Created, but I wouldn’t dive into this thinking that it’s definitely not covered. I think working with the provider, even if the provider doesn’t take your insurance, but talking through and being persistent with your insurance company does pay off. In my experience.

Gene 30:18

Does somebody put, are there folks out there who parents can consult with? You mentioned the pediatrician, and that’s excellent. Are there other folks that they can talk to, just to get a sense of here are the things that I’m worried about. How should I go about getting from what I’m observing and what I’m worried about to actually getting the testing done through the school or through a private individual or through a clinic?

Ellen Braaten 30:54

So, I find that the teacher is your number one ally in this 90% of the time, and when they’re not, that’s when things can get really difficult. But talking to other parents too can be very helpful and useful, and that’s how a lot of parents negotiate this very complicated system, by talking with other parents who also have been through the same system. So, the pediatrician, other parents, other family members, and relying on the teacher, and I think Eileen mentioned before too, a lot of the kids that I evaluate privately are kids for whom the teacher said, Listen, you got the evaluation done at school. I did not tell you this, but mortgage your house to get this done, because you really, you’ve you your child is really, like, not making it, and should be. And so I do find that that’s the, you know, one of the things that’s best to do, the best you the better you’re educated as a parent, listening to podcasts like this, knowing what to look for and is your best bet at being a good advocate for your child.

Gene 32:09

And there are places to look at the Clay Center site. I mean, we do have a bunch, in fact, you wrote most of them about slow processing speed, about attention deficit disorder, about dyslexia, about all sorts of you know, being on the autistic spectrum, whether it’s mild or moderate, you’ve written a lot. So, there’s so there are resources available, right?

Ellen Braaten 32:35

There definitely are, yeah,

Eileen Hagerty 32:37

And parents can also. They could consult a special ed attorney. They could consult a special ed advocate. There are many lay advocates who practice in this area, who advise parents. There are also free resources, helplines, hotlines, I know at Mass Advocates for Children, we have a helpline the three that people can call. And there are other similar resources in other states in terms of evaluations, I did want to mention also there is a federal right, and in our state, also a different state right for an independent educational evaluation at public expense. Which to activate the federal right, you have to have the school district evaluation first, and the parent would have to disagree with it. And the downside to that process is, if the school doesn’t agree to give the requested evaluation, then you end up in litigation pretty quickly, which most people don’t want, especially over sort of a subsidiary issue like that. In Massachusetts, we also have a needs based, sort of track you can go for an independent evaluation. But that is not in every state. So, and either way, I think that there is a concern, what Ellen was talking about, that good evaluators, even if you’re paying out of pocket, the good evaluators, you’ll have to wait. Parents often have to wait to see them, and if you are, if parents are limited to publicly funded ones, whether through publicly subsidized insurance or through these statutory rights to an independent public, an independent, valid public expense that can take even longer to find somebody who can get you, you know, provide one of those slots. But it’s definitely worth, you know, worth, worth doing.

Ellen Braaten 34:23

I should mention too just while we’re on this topic of who else to help can help. Another way of getting support is to get the evaluation done through the school and consult with a psychologist or a psychiatrist who is who really has a lot of information on this. So, to bring the school evaluation to someone like me, we do that at the at LEAP, at Mass General, but lots of psychologists do this that will just do a one hour consult. You’re talking about a couple $100 few $100 as opposed to a few $1,000 and it might give you enough information to go back to the school. School and enough information to be able to advocate.

Khadijah 35:04

Those are, those are, go ahead. Eileen,

Eileen Hagerty 35:06

Let’s just say certainly if the student already has the provider in the area you’re worried about, student already has a counselor, student already has a private speech therapist or occupational therapist or whatever, Yeah, take that report from the school to that person and get their feedback, or even if you’re trying to decide whether to request the evaluation from the school, consult that person for sure.

Khadijah 35:29

These are really helpful tips. And I think, you know, knowledge is power. And you know, the for a system that’s so big and often so difficult to navigate, even from the most, by the most savvy, of people. I think these are really great tidbits. I just want to go back a little bit to talking a little bit about some of the legal aspects and what rights are guaranteed to children and parents. And we discussed some of the aspects, such as, you know, they have a right to a special education, parents have a right to be a part of the team. But what about some of the other things that we kind of touched upon, but like things like a Right to an Independent Evaluation. There are things like the state put rights or unilateral placement. How do these things kind of come into play from a legal aspect, and how do these things serve parents?

Eileen Hagerty 36:12

Well, IDEA has a lot of procedural protections for parents, as we mentioned, has many more specific protections than 504 does, although some of the 504, some of the idea of protections have kind of been read into 504. But yes, as you mentioned, there’s the right to request an evaluation, the right to have an evaluation, the right to participate as a member of the IEP team, the need for prior written notice of any, basically anything the school district, anything significant the school district is proposing to do, whether it’s to propose to propose an IEP, propose an evaluation, propose a placement, propose a reevaluation. They need. They need to provide written notice to the parent in the parents, you know the language used in the home that goes through a number of specified things, including it’s basically what they propose to do and why they propose to do it, and what, what other options they might have considered and rejected. And so, then the parent has the right to consent or withhold consent to an IEP or an evaluation or a placement. Right to an independent evaluation at the public expense we talked about a few minutes ago. Right to an independent evaluation at the parents’ own expense, they can get that at any time, and then, if they get an independent evaluation report, they give it to their school district. The district is required, if the students already in special ed, at least, the district is required to convene the student’s team within 10, within. Well, no, I’m in Massachusetts within 10 school days. IDEA just says they’re required to consider the report. The team is required to consider the report. Not necessarily follow it, but consider it. Stay put rights, you mentioned Khadijah, that is the right in the event of a dispute over the student’s services or program replacement. If the parents reject all or part of the district’s proposal to change those aspects of the program, if the parents were happy with the student’s program, let’s say, and then the district proposed an entirely different model, or proposed to eliminate some services or propose to move the student to a different school, whatever. The parent has the right to reject the proposed change and insist invoke the child’s stay put right, which essentially has the child stay in the last agreed upon placement until either the school district and the parents reach an agreement, or the or the matter is litigated to its conclusion. There are a few exceptions for school discipline, some school discipline situations, and so on. But in general, stay put, is a valuable right. Unilateral placement that refers to the parents have the right if, again, if there’s a dispute about the student’s placement, the parents have the right to place the student themselves in a program different from what the school is recommending. Usually, it’s the private program, and there’s a notice requirement and so on. But then they can seek reimbursement from the school district for the expenses connected with that program, including tuition and transportation, and so that is a route that parents sometimes take if they can afford it. Obviously, it’s not always feasible for everyone. Let’s see. I mean those I would, I would say, are some of the most, the most basic rights in idea. Obviously the right to FAPE, free, appropriate public education is kind of a baseline right. But the specific procedural rights that the parents have are some of the things we’ve just been talking about. I should mention also, there’s a right to dispute resolution procedures. IDEA specifies two types, well, two types of formal dispute resolution proceedings. Well, I wouldn’t even say they’re both formal. One, is the right to mediation, which has to be provided by the state, offered by the state free to the parents; and if the school district and the parents agree to mediate, then the state provides a mediator to discuss the dispute with them; and if they reach agreement, it’s written up and it becomes a binding contract. If they don’t reach agreement, the parent still has all of their rights to proceed to use the other dispute resolution procedure required by IDEA, which is a due process hearing, which is a more formal it’s an administrative procedure, not a court proceeding, but it’s similar to a court proceeding, in that a hearing officer takes evidence. Evidence is presented on the record, cross examination, direct examination, opening statements, closing statements, like a trial, and then the hearing officer issues a written decision which is appealable to court, state or federal court, so that those two any state that accepts IDEA funding has to make those dispute resolution options available. And of course, parents and districts can speak informally at any time. That’s often the best if they can just informally resolve their disputes without having to go to mediation, or certainly without having to go to hearing but again, that sometimes it’s possible to resolve disputes fairly quickly and easily, and sometimes not.

Gene 41:31

So, we have we only have a limited amount of time, but I just wanted to get a question or two filled in. Very briefly, you know these, this is all based on public, publicly funded schools. There are lots of folks out there who send their kids to parochial schools or private schools. What? What rights do they have to get this kind of testing done, or is this? Are they on their own?

Eileen Hagerty 41:45

No, they do have rights to an evaluation. Fortunately, they’re not entirely on their own. They have rights to an evaluation like any other student would. If they’re found eligible, however, under federal law, they’re not entitled to an IEP, they’re not necessarily guaranteed services. The Federal right for private school students is a group right to so called equitable participation, or proportionate share participation. If there are 10% of the students attending school in a district who are attending private schools. Than 10% of IDEA Part B funds, the special ed funds, are to be devoted to private school students. But that doesn’t mean students have any individual right the district and the private schools located within the district have to consult about how to use the funds, but they could use it for one student or one group of students or students at one school, or to buy some, I don’t know, equipment that might benefit a lot of students. So, it’s not under IDEA. It’s not the same kind of right as it is under as it is for students who attend public schools. However, if a student is found eligible, they could take that determination, and then go to their public school and enroll and presumably have a team convene and develop an IEP for them. And I should say that some states I know Massachusetts has does have individual rights for private school students under state law. Which gets kind of confusing, because under state law, it’s the district where the student resides that’s responsible to meet their needs, and under federal law, for private school students, it’s the district where the private school is located. So, this can get confusing, but again, it’s worth checking state law, because state law may provide more rights for private school students than federal law does.

Ellen Braaten 43:57

and I should say too that in reality, what happens in a private school is, if you have an evaluation done through the school system or privately, they will develop something that most private schools will develop, something that looks like an IEP. It doesn’t have any of the same legal rights or anything like that. But sometimes they’ll call it an accommodation plan or a learning plan. So, private schools oftentimes will try to do something like that. But again, no, no sort of legal, you know, safeguards beyond that and the other thing. And Eileen, maybe you could comment on this that I find that even in like, let’s say, a child is diagnosed with dyslexia and wants to go to the school to get the tutoring for dyslexia. Most of the time they have to actually go to the school. So, if they’re in a private school, the public school does not have to provide that service at their private school. So, it becomes something like a difficult sort of thing when they’re a sixth grader and they have to travel to public school to get their reading or writing tutoring.

Eileen Hagerty 45:05

Yeah. So, if, if a private, if a public school district is going to provide services to a student in in private school, sometimes you’re right. Sometimes the public school district proposes, okay, private school student, you come here for your services and transportation can be an issue too, about who is responsible for that. Federal law says that services may be provided by the school district at the private school if the services are neutral and non-ideological. So, it is possible, under IDEA, for public school teachers or other providers to go into a private school to give services. However, in Massachusetts, the reason we don’t see that much. We have a so-called anti-aid amendment that basically has been interpreted to prohibit that. But I believe in some other states, we see more of public school staff going into private schools to provide services. And then sometimes, sometimes students who are who attend private schools are identified with a disability. I’ve seen it happen, and you probably have too Ellen. That maybe for a year or two. I was young. They go along. They’re at the private school. Maybe they get some services from the public school district, whether it’s at the public school or somebody coming in, but then at some point it may become clear, well, either that the student is remediated, and that’s right, and they don’t need the services, or maybe those services aren’t enough and they need to go to the public school and enrol, there to get the full amount of services they require. Because if you have a student with severe learning disability, severe autism, whatever, if they require a small, self contained, specialized classroom with similar peers, etc, you’re not going to have that at a private school. You only, well, not at a private school of the type we’re talking about, you would either need to go to public school or to a private, specialized, special ed school.

Gene 47:09

I think it’s a cool question, but it’s it has to be real quick. Is if, if, if your kid gets an IEP or a 504 this may be the subject of another podcast, but maybe Ellen, how do you how do you talk with them about it?

Ellen Braaten 47:26

Well, okay, let me think about this. How to be all right, so first of all, the IEP is something that is formulated by a team, and I think that’s something we haven’t talked about.

Gene 47:40

We may need to schedule another podcast, but, but that’s okay.

Ellen Braaten 47:44

Might not be a bad idea. I think this is it’s a big topic. So an IEP is developed from a team, so everybody brings their own view of the child, their own data about the child, if they’ve done a formal assessment, to the team, and the team develops a plan that will meet that child’s needs, and that plan usually addresses something that needs to be changed in the curriculum. And Eileen correct me if I’m wrong about this, but a 504 plan is developed to have accommodations that the child needs within the normal curriculum, but but may need, for example, an accommodation might be a child is hearing impaired needs to sit in a certain spot in the classroom, or a child with ADHD has difficulty paying attention and may need certain, you know, places to sit in the classroom, or certain things put into place that will help them focus their attention. But the plan is not a 504 plan does not change the curriculum. Whereas a child with dyslexia, for example, needs a different way of learning to read than everyone else in the class who’s using the typical curriculum for the school. So that’s the biggest difference between the two, is one is really changing the instructional approach, and the other is helping to accommodate a child’s disability. So, both. That’s the biggest distinction between those two.

Khadijah 49:18

Thank thank you for sharing that that’s going to be really helpful, and I know we are running short on time, so I really wanted to thank you, Ellen and Eileen, for the time that you gave us today. Thank you for sharing your personal stories. I think this is really helpful for families who are trying to navigate this complicated system, and we really enjoyed and really enlightened by the conversation that we had today. So, thank you so much for your time.

Eileen Hagerty 49:44

Thank you so much. Very happy.

Ellen Braaten 49:46

Yes. Thank you so much. It was great to see all of you!

Gene 49:49

And maybe we’ll have you back. If this, I would love to. I would love that. So, for those, if those of you at home listening, if what you’ve heard today, consider, you know, consider leaving us a review or asking questions. Get involved, and as always, we hope that our conversation will help you have yours. I’m Gene Beresin.

Khadijah 50:14

And I’m Khadijah Booth Watkins, until next time.

Episode music by Gene Beresin

Episode produced by Spenser Egnatz

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet