Navigating Special Education in Schools Part 2: Working with the Team and Your Child

Posted in: Multimedia, Parenting Concerns, Podcast

Topics: Hot Topics, Learning + Attention Issues, Mental Illness + Psychiatric Disorders

This is the first blog post in a two-part series on navigating special education in schools. The focus of this first post is on general legal and practical tips for parents. The second post focuses on working with the IEP and your child.

The Special Education system in school can be confusing, especially if you haven’t been through the process with a child before.

In part 2 of this series, Gene and Khadijah continue their discussion with Ellen Braaten, PhD, and Eileen Hagerty, Esq, who specialize in learning disabilities and special education law. They discuss evaluation results, advocacy, and the importance of destigmatizing special ed.

Media List

- Learning & Emotional Assessment Program (LEAP) (MGH)

- Ellen Braaten, PhD (MGH)

- Eileen M. Hagerty, Kotin, Crabtree & Strong, LLP (KCS Legal)

- Massachusetts Advocates for Children (Mass Advocates)

- Navigating Special Education in Schools Part 1: Legal and Practical Tips (Shrinking it Down)

- Wrightslaw Special Education Law and Advocacy (Wrights Law)

- From Emotions to Advocacy by Pamela Darr Wright and Peter W.D. Wright (Wrights Law)

- Parents Have the Power to Make Special Education Work (Amazon)

Episode Transcript

SPEAKERS: Gene Beresin, MD, MA; Khadijah Booth Watkins, MD, MPH; Ellen Braaten, PhD; Eileen Hagerty, Esp.

[INTRO MUSIC BEGINS]

Ellen Braaten 00:00

Understanding is key, because you want to be able to advocate in the future, and you want to be able to convey your child at different points in their development, what this all means, like, what what can they expect? What might be the challenges for them? What are their strengths that they can capitalize upon.

[INTRO MUSIC ENDS]

Gene 00:28

Welcome back to Shrinking it Down: Mental Health Made Simple. I’m Gene Beresin.

Khadijah 00:32

And I’m Khadijah Booth Watkins,

Gene 00:34

And we’re two child and adolescent psychiatrists at the Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds at the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Khadijah 00:42

Last episode, we discussed the basis of the special education system. We discussed the basic definitions and what the rights are, what rights are guaranteed for parents and students, and some of the aspects that are involved in the process of requesting accommodations through either an IEP or 504.

Gene 00:58

And now today, we’re going to be continuing our series on navigating the special education system, which I think is probably of all the issues that come up with when I work with parents, caregivers, families and young people, I think this comes up probably as much, if not more, than anything else. But today we’ll be focusing on individualizing your child’s plan with their team, and to help make sense of this, we’re delighted to welcome back our two special guests, Dr Ellen Braaten and Eileen Hagerty.

Ellen Braaten 01:33

It’s great to be back.

Eileen Hagerty 01:35

Thank you. So glad to be here.

Gene 01:37

And so, to briefly introduce for those of you who haven’t heard episode one, and I would encourage you to go to our podcast and listen to the first episode, which kind of sets the stage for this follow up one. Ellen Braaten is a PhD, the Executive Director of Learning and Emotional Assessment Program that is the LEAP program at Mass General Hospital, and founder and and co director of the Clay Center, and we miss you at the Clay Center, Ellen.

Ellen Braaten 02:08

I miss you guys too.

Gene 02:11

Well, we see each other a fair amount, at least online. Dr Braaten is widely recognized as an expert in child and adolescent and young adult psychological assessment, particularly in the areas of assessing learning disabilities and disorders. So, it’s great to have you back again.

Ellen Braaten 02:29

Great to be here. It really is.

Khadijah 02:32

And I have the pleasure of reintroducing Eileen. Eileen Hagerty, Esq. is a partner at Kotin, Crabtree and Strong in Newton, Massachusetts and has concentrated her practice in special education law since 1998. Prior to joining Kotin, Crabtree and Strong, she worked as an Assistant US State’s Attorney and as a special assistant district attorney. Eileen lectures and writes frequently on topics in special education law for both legal and lay audiences. She also participates in various public service activities, including serving on the board of directors for the Massachusetts Advocates for Children. Welcome back, Eileen,

Eileen Hagerty 03:07

Thank you, Khadijah. I’m so glad to be here.

Gene 03:11

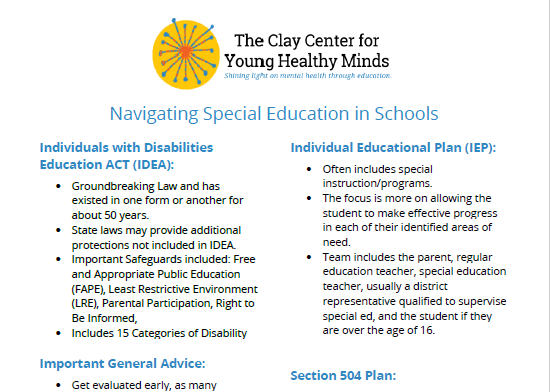

So, let’s start now. For those of you who don’t know, an IEP is an Individual Educational Plan, but let’s start you know, Eileen, if you can tell us what, who is largely on an IEP team?

Eileen Hagerty 03:30

Well, the federal special ed law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, known as IDEA, specifies who is on the dean and state law, as we talked about before, state law can provide additional protections too. So anybody is well advised to check their state law as well as federal law. But IDEA says the first so IDEA when they list who should be on the team, number one, the parents. Parental participation is very important. Teams cannot meet without the parents unless they they’re required by law to take steps to try to ensure parental participation. They can only meet without parents if they’re unable to convince the parents to attend, or if the parents refuse to attend, the parents are always a very important member of any and then IDEA says there should be at least one regular education teacher on the team, if the student is or maybe spending any time in the regular ed setting, there should be at least one special ed teacher or provider on the team. There must be a representative of the district who is qualified to supervise special ed and who knows about the general ed curriculum as well, and who knows about the resources that the district has. And I would add who could commit the district’s resources, who can make decisions, and then there has to be someone on the team who can interpret evaluation results. Now that can be one of the people I’ve already named, like a special ed teacher or the district representative, or it could be someone else, the child as appropriate. The statute says may be invited to participate in the team discussions, and that usually means a student who is approaching so called transition age, the students who, under federal law, be students who whose IEPs are going to be developed, but the student would be required to be invited for the IEP to be developed when he or she is turning 16 or beyond that. A student doesn’t have to attend, even if, even if the district is required to invite that student until the student becomes legally an adult and is making their own decisions before that, it would be the decision of the parents whether it be the child’s best interest to attend or to attend part of the meeting. And then the statute says, at the discretion of the parents or district, other individuals with knowledge or expertise may be invited to the team meeting. So sometimes parents want to bring the outside evaluator, the independent person from own program or wherever, or a tutor or a speech therapist or someone who’s worked on the outside with with the student and parents in the school district can agree to waive the presence of any of these individuals, but this is what the step requires, and then those people come together for the so called Team meeting to discuss evaluation results and develop an IEP, Individualized Education Program.

Gene 06:26

So let me just follow up quickly. I, you know, we talked a little bit about this before, but IEPs can include both cognitive or or process, you know, academic or problems with learning and also social, emotional and behavioral problems. And secondly, they can the plan could either be an Individual Educational Plan or what we call a 504 plan, which is accommodations. So could you comment a little bit about how parents and caregivers can kind of really think about the academic or learning problems, the social emotional problems, and whether or not they merit an Individual Educational Plan or 504 which is special accommodations.

Eileen Hagerty 07:15

Right? So, so an IEP can address, well IEP or a 504 plan may address emotional, psychological, behavioral issues, as well as the more strictly academic issues, issues related to intellectual disability or learning disability, something like that. The difference for an IEP, at least, it would have to be a condition that has some effect on the child’s education. So if the student is perfectly well behaved in school and falls apart at home and has meltdowns and so on, it’s going to be harder, at least, to get an IEP to address that than when the school can see the effects of a behavioral or emotional disorder in in the school, but, but yes, it. Parents can ask for an IEP or a 504 plan for, you know, basically any type of disability that has an effect on the on the child’s performance or participation at school. I think we mentioned last time, 504 and by the way, an IEP team and a 504 team are different. The requirements I just listed for members of the team. That’s for an IEP team, a 504 team, basically very few requirements. It’s just supposed to be a group of people with knowledge about the student. 504 doesn’t even specifically require the parents be present, although it would be good practice to invite them, certainly and for them to participate. And the one team doesn’t decide you get an IEP or a 504 there are two separate it’s two separate avenues, and I think we mentioned last time, the purpose of a 504 plan is to allow the student access to accommodate his or her disability, so that student can participate, basically to level the playing field, so the student has the same ability to participate in educational and extracurricular type activities as non disabled students. An IEP, the focus is more on allowing the student to make effective progress in each of their areas of need, and it’s really relative more to themselves and to their capabilities and where they start out looking at, how can they make progress in their areas of need, as opposed to, how can we level the playing field so they can participate like other students.

Ellen Braaten 09:37

So Eileen, can I just jump in and ask you, if I explain this to my families, that I assess correctly, that the simplest way that I say the difference is, is that an, a 504 plan is really to accommodate your child’s learning, but they don’t need a different kind of program that you might need, or you would need in the IE. So, an IEP they need a different sort of program to learn to read, for example. And a child who might be diagnosed with dyslexia when they first get the diagnosis needs a whole different kind of reading program. And then when that different change in curriculum works, the child may then graduate to a 504-accommodation plan, meaning that the learning disability is all always there. But at one point in their education, they may need a different program. And at a different point in their education, they may need to be accommodated, meaning they might need they might still be a slower reader. They don’t need a full new kind of program for that, but they need that slower reading to be accommodated. Do I? Am I explaining that correctly to parents? I know it’s sort of simple compared to, you know, sort of legal definition.

Eileen Hagerty 10:49

Yeah. I mean basically, yes. I mean some people say, well, 504 plans are for accommodations. IEPs are for services. It’s not, it’s not quite that simple. Because, as I’m sure you know, students on IEPs also often get accommodations that are listed in their IEPs, and students on 504 plans can get services. It’s less common, but they can if needed to level the playing field. But you’re right that to be eligible for an IEP the student needs not only to have a disability in one of these, you know, categories in the statute, but they also need to require specialized instruction, special education and well, in some states, requiring a so-called related service like speech therapy or occupational therapy or physical therapy would also qualify them. That varies by state, but you’re right. They have to need some kind of instruction, or, in some states, related service that is not part of what’s provided in the general ed classroom, and it’s a specific methodology designed to meet their special needs. So yes, I’d say you’re defining it well.

Khadijah 11:56

So, when a parent requests an evaluation for their child through this from the Committee on Special Education, at the end of the evaluation, the committee decides whether they get an IEP or 504 is that? Is that what you

Eileen Hagerty 12:13

Well, the students IEP team or 504 team decides whether they’re going to get an IEP or 504 and if they are going to get it, that same team decides, or should decide, what, what is it going to contain, what’s it going to propose? And there’s also the question, where is it going to be delivered? What is the child’s placement going to be? In some states, that’s required to be cited by the same team, and in others, it’s allowed to be made by a separate group of people, but the parent is, so the team under the IEP process, and actually under 504 too. It’s a slightly different team, but the team is a key. The team is the one that makes the decisions about eligibility and about the services the student is going to get. However, it’s not. So, a team can be large. It can sometimes, I’ve been at meetings where they’re eight or 10 or 12 people, sometimes isn’t always. And you think, well, maybe they take the vote. But it’s not quite that simple. If there’s no consensus in the school district, is the one that develops, that makes the decision and develops the IEP or 504 plan, and then the parent has the right to challenge anything about that if they don’t like it, but, but it’s not so the parents have to be part of the IEP team. But it’s not quite so simple as taking a vote. This is what I would say.

Khadijah 13:41

Okay, and so at the end of an evaluation, there’s lots of data to be interpreted. How? How are the different evaluations, results of the evaluations, interpreted and then conveyed to the parents, the IEP team, the school?

Eileen Hagerty 14:00

Well, first of all, evaluations are required to be in writing, at least under IDEA, and I believe under 504 also. So, the parent is going to get those written results. And under IDEA, it needs to be provided in the language that the parent speaks. But then the conclusions and findings will be discussed further at the team meeting at which knowledgeable people are supposed to be present. I think some parents do find the whole process overwhelming. IDEA also doesn’t specify how far in advance or if, if they need to be given the written reports in advance, so that can be daunting, if it’s passed out at the meeting or the day over the day before. I think if parents have an independent result, and I think Ellen may want to speak to this, if parents have an independent evaluation, then they could speak with the independent specialist who would perform that evaluation, and that person may also be able to help them interpret the school’s evaluation result.

Ellen Braaten 15:09

Yeah, I think that’s true. Yeah, my experience with working with parents who have school evaluations and being a parent who had a child who had school evaluations. I, parents generally receive the report, the written report, it’s written at a level of like college reading level. This has been analyzed in many studies, and so it’s not very understandable for the average parent. Most parents don’t know what the sort of statistics that are used in the report are, and they get almost no explanation. So, for example, a typical sort of evaluation may include an occupational therapy evaluation, a teacher, you know, a special education teacher, doing a portion of the evaluation, a school psychologist and a parent will get sometimes four or five different reports. It’s hard to know what it actually all means, typically. And I’d love Eileen to talk about this, because typically, they do not include recommendations in the report, and so that makes it even harder to interpret. So, you have all these numbers in the report, and there’s no diagnosis at the end. There’s no recommendations, because that’s made as a team. So, the parent is just there with this information that they don’t even know what it all what it’s all about. So, my experience is that parents get actually very little to no explanation of what the evaluation says, the written evaluation, and then they’re at a team meeting, and oftentimes, like Eileen said, it could be 10 people. Well, how well do we really listen to important information when we are sitting there surrounded by 10 experts, it’s usually not very, very good. We’re not able to take it in. And each expert typically only gets two or three minutes to explain their evaluation, so it’s a tough process for parents. I don’t mean to make this sound hopeless at all. I mean, that’s the point of this is to help parents be more educated, but it’s it’s not a great and informative experience for most parents,

Eileen Hagerty 15:37

The lack of recommendations is a huge issue in my experience with school evaluations, even though, in our state, under our state law, in Massachusetts, they’re supposed to, schools are supposed to recommend explicit means of meeting the child’s needs. I think it’s a regulatory language, but often doesn’t happen. I think parents should push to get the reports as soon as possible, so they aren’t scrambling to read them and listen at the same time during a team meeting, and then, if possible, because I said, ahead of time, with someone who can help them interpret it, and at the meeting to ask questions. There are no stupid questions. People shouldn’t feel that way. So, if you don’t understand something, parents should ask. And if there are no recommendations made, well, presumably recommendations were made at the team meeting, but again, they can ask.

Khadijah 18:12

I agree, Ellen, I’ve looked at some of these reports, and I was like, wow, there’s a ton of information. And even being a clinician, you know, it’s hard to digest. So, how is a parent to digest all this information? Like, I understand it’s important for them to ask questions, but what are some questions that we can help parents’ kind of be armed with when they go into these meetings, to think about asking. You know, how do they how do they think about what are the next steps?

Ellen Braaten 18:41

I think one of the things they want to do is to just not be afraid to ask questions. Not be afraid of the experts. They are experts because they have information that the parents need. That’s what makes them important, and that’s what parents need to ask for. So, I often encourage parents to ask to meet with the school psychologist, even after the meeting, and I Eileen would say whether or not that’s a legal obligation, but it’s an ethical obligation on the part of the psychologist. And so, parents can say, you know, we had our team meeting. I agree with the with what was done, or maybe not agree, but let’s say they do agree, but they can go back and say, but I don’t really understand any of it. I need you, as the school psychologist, as whoever is that the head of the Special Education team, to explain this to me more. So that’s one route is they can ask for more information. The second route is to go some to someone like us, like you know, a psychologist, a psychiatrist who’s trained in this, they can if they if their child already has a therapist, they can go to their therapist or psychiatrist and say, “Can you help me understand this?” If they don’t have somebody there are lots of people in private practice or in hospital-based practices that do a consultation on this, and they can bring their information, they can bring the report to a specialist and say, Listen, this is what happened. I’m happy with the level of services, but I still don’t understand. And understanding is key, because you want to be able to advocate in the future, and you want to be able to convey to your child at different points in their development what this all means, like, what can they expect? What might be the challenges for them, what are their strengths that they can capitalize upon? So, being able to digest that information is really important. So, either get more information from a trusted professional at the school or get information from a trusted professional in the community, and it doesn’t have to be 10 different sessions, like in 45 minutes, a professional who understands testing can usually give parents an awful lot of information about how to interpret that data.

Khadijah 20:54

Now, Ellen, you mentioned not agreeing. What if a parent doesn’t agree with the results of the testing or the report?

Ellen Braaten 21:01

Well, then I’m going to let Eileen talk about that. What the next steps are for that. But let me tell you, from a nuts-and-bolts situation, you need to be uber informed as to what this means. So, you need to really be able to understand and have someone on your side, on your team, who can help convey the importance of the information that was gained and what that means to the child’s learning now and in the near and far future. So, if you don’t agree, that’s even more of a reason to seek more information, and I do really, I might say it might sound like I am anti-school, and I’m really not there. You know, most of the people working in school systems are super dedicated and wonderful professionals, and so use them like, go to the person that you really trust. If you really feel like, boy, we have come to an impasse, and this is not working. It’s even more important to get informed and going to professionals, psychologists, psychiatrists, other people in private practice, going to your pediatrician as a start. If you don’t even know where to start, pediatricians do have you know. They do have knowledge about this, and they can point you in the right direction. And then also getting information from other parents. There are different organizations, different state and local organizations, SpEd PACs, Special Education Parent Committees, or I’m not even sure what they’re what that stands for, but different organizations in communities where there are other parents who have lots of information to help parents navigate this situation.

Eileen Hagerty 22:46

If I could just add quickly, we’re talking a lot about experts, and experts are important. But parents should remember they are the experts in their own child, and if something doesn’t seem right about the school psychologist’s take on your child, or the independent psychologist, or the OT or whoever you know, or if there’s some nagging doubt in your mind, they say, my child isn’t eligible, but he’s still having trouble with reading or whatever. Parents should listen to that.

Khadijah 23:12

And so what should, what should they? What can they do if they don’t agree with the results?

Eileen Hagerty 23:17

So, when the team needs to develop an IEP, then followed by the written IEP being delivered to the parents and reject that if they reject it, either entirely or in part, if they disagree with it. And then there are procedural safeguards that include states have to provide a mediation option for parents and school districts who want to try to mediate disputes over anything at all, eligibility, placement programs and then their states also have to provide a formal due process hearing avenue for people to pursue. So, mediation has to be available, but that’s voluntary if the parties want to pursue it. The due process route is not voluntary, in the sense that one party starts at either the school district or the parent files a hearing request. And then there’s a procedure that’s like a trial, although it’s at the administrative level. And then there can be appeals from that decision to in some states, to an Intermediate Review Board, and in all states to state or federal court. So there, there certainly are formal dispute resolution procedures. But I guess I’d circle back to what Ellen said, if you have an if parents have a doubt, a problem, a disagreement, it’s always, almost always, best to try to sit down informally, first with someone at the school district, whether it’s the team, fair person, special educator, whoever, or the person you trust most at school, and see if you can resolve it informally, and if not, you do have these other options.

Gene 24:50

So one, one thing that I’d like to to shift a little bit is to as to how parents can, prepare and help the kids get through the testing. So maybe Ellen, you could, you could start, since you’ve been in this situation before, you know, two questions, really. How do you how do you prepare your kids at different developmental levels? Or what this testing is all about? Because getting them in the right frame of mind. I mean, I know plenty of kids that I’ve seen you know they just they need to kind of understand what this is for and how it’s going to help them. So how do you do that? And then, once you get the results, how do you explain the results to your kids?

Ellen Braaten 25:39

So, starting with the first one, there’s really two parts to that, in terms of preparing your child. If your child’s getting evaluated in the school system, they won’t know it. You really can’t prepare them for it. They will have no idea what day the testing will happen. It will often be done in little bits and pieces. So that means that they’ll be just taken out of math class for 20 minutes with the school psychologist, or maybe they’ll be pulled out of lunch. So it’s very hard. And in fact, I would say most kids don’t even know they were evaluated at school because they’re just working with another specialist they don’t even know. And so that’s a tough one, because at school, it can really, you know, if you really say you’re to your child, you’re going to get an evaluation at school, and you need to be prepared for this. They, it could be two, three weeks before anybody even does anything, and they might the person evaluating them probably isn’t even telling them what they’re doing, to be honest. So that is a question without a good answer. Now, if they’re getting it done privately, that’s a different situation, because then what you can do is talk about, first of all, developmentally, you want to meet the child where they are. So, if they don’t really have any idea that they’re even struggling and reading, for example, or in first grade, they think everything’s great. What you can do is really sort of convey that, you know, you’re meeting with somebody who understands kids learning styles, and many kids get this done. I think that’s it’s really a true statement that you know, at one point or another in development, most kids have something like this done, and we’re going to see somebody, you’re going to be doing a number of different things with them that will help us figure out how you learn best. I sort of say it needs to be as matter of fact as possible. Don’t make kids feel too overwhelmed by it. As kids get older and developmentally, understand that they’re struggling. This is a way of really building an alliance with your child and saying, I see how difficult certain things are, we need to understand this, and so we’re going to see somebody that is going to help us, and your teachers understand this. And you don’t need to be nervous about this because there’s no like, it’s not really a test that has right or wrong answers, it’s an, it’s the kind of assessment that just helps us understand better. So, just be yourself, and you probably will find it kind of fun, which is true most kids find, you know, a good majority of it sort of interesting. So, it’s really different, whether it’s the school-based assessment or not. In terms of, oh, go ahead.

Gene 28:16

No, no, I was just going to say. And okay, so the testing is done, the team meeting happens, there’s some results, and there’s a plan. And so how do you talk to your kids about the results and what they mean? Because some, any of the older kids, especially, will be curious, like, what you know? What’s, what are my strengths and weaknesses? They need to know this. So how do you, how do you, how do you interpret the results?

Ellen Braaten 28:40

So, what you want to think about throughout however you decide to speak to your child about this, and some kids, they just want to know the basics. I’m fine, good. That’s great. I don’t care what you know what’s happening in school, as long as you guys have it all planned out, I’m in. And other kids want to know that every little detail. But what you want to keep in the back of your mind is something called a growth mindset, meaning that we want to have this mindset, that we’re using this information to help a child grow and understand themselves better. So, a growth mindset really means that we’re sort of in-sync. We understand, like, for instance, how the brain works. And kids love to know that. They love to know that these, you know, whatever we’re talking about has to do with, you know, brains, and how brains work in a very positive way. And so, think about that. We’re using this information to help our child understand themselves better. Some kids need a lot of that, a lot of information. They do better with that, and other kids don’t. So, know your child, and then you want to relate the results to sort of a feeling of like, oh, you we know what we’re doing now. I’m so glad we did this assessment our I’m so glad your school did this in late they looked at how you learn to read or learn to do math or your behavior. We know now what to do, and we’re going to do our best to make sure you get this consistently. In a way that’s going to make school much better for you, and it’s it doesn’t you don’t want to do anything that’s conveying any sort of blame on the child, but understanding everybody learns differently. And wonderful, wonderful news, we found out how you learn differently, and now we know what to do if there’s a diagnosis which there oftentimes isn’t a in a private evaluation, out of school evaluation, know your child well enough to know whether or not a diagnosis would help them or if it would get in their way. So, using something like ADHD, for some kids is like, oh, I have ADHD. That’s why it’s hard for me to pay attention. And for other kids, it feels like a real sort of stigma to them. Know your child and what your child, how they’ll react to that, but these results should be conveyed in a way that we’re so happy we know what to do we now as adults, it’s our job to put that in place for you, and we are going to do our best to do it. And if it doesn’t work, we’re going to come back around to this and we’re going to figure it out again.

Khadijah 30:59

That’s awesome, how to put it in that growth mindset and to really, especially with the older ones, make it a collaborative process around it’s a team. We’re going to help you. We’re going to work together to help you. That’s really nice. I just want to talk a little bit about, a little bit more about kids. So, in working with kids, I often hear kids complaining about being pulled out or going to separate classrooms or having to take speech. You know, I have kids that outright refuse to go to, you know, their resource room or to some of their services, and I know that fitting in is so important for kids, especially as they grow. How do we talk to kids about stigma and help them feel less alienated by, you know, some of their accommodations that they might have in their IEP, or 504?

Ellen Braaten 31:44

So, I think the more kids understand about the learning difference, the better, the better they can handle whatever stigma is there. So, you know, helping them understand that what, what does having ADHD means? It means this, and it’s sort of like, oh, it’s not something worrisome, because a lot of times there is stigma, there is teasing, and that’s a different it’s almost like that’s a different aspect that I would love Eileen to address, because oftentimes what I find is the reason why kids don’t want to go is one the school’s not handling it well, meaning that they are not doing a good job of making kids feel like they are not being stigmatized, meaning that the way that the services are being delivered is stigmatization in and of itself. So, I don’t know what rights parents and kids have in that situation, but my first question is always, can we have these services administered in a way that’s more developmentally appropriate for a child, like it’s not okay for a sixth grader to be pulled out in the middle of history class to go get their reading tutoring. That’s just not okay. And then the other issue is that I often find that kids don’t want to go to their other sessions because it’s not very helpful, or they haven’t linked the fact that what they’re getting is going to help them in some way. So, to me, I’m always my radar is always up. You know, yes, I want to help the child feel better about what they’re doing, but my radar is always up. When a child’s like, I don’t want to go. It oftentimes means to me that something’s not going right. Because typically when a situation helps a child, they typically want to go, especially if it’s done in an empathic kind of manner. So, my, I’m, I’m always thinking in that sort of situation, yeah, I want to help the child, but really, I probably need to figure out what’s going on to make the child feel that way in the first place. And I would ask Eileen, are there like are their rules that parents rights that parents have in these sorts of situations?

Eileen Hagerty 33:53

Well, first of all, I agree with you that stigma and alienation can be a big issue, especially with middle and high school kids who are more attuned to what others are thinking of them, and the special ed laws have confidentiality requirements. So, it would be illegal, for instance, for the teacher on the first day of school to put a list on the whiteboard or whatever of who’s on an IEP that just that would just be, you know, wrong in a few different ways. However, kids aren’t stupid, and they notice who’s being beckoned out of class, or who’s going into the resource room or whatever. So, they, do know it seems to be well known, usually, who’s who, who is getting special services, even though the levels of special services are, you know, something like 20% in Massachusetts, I think so. You know, it’s not like it’s a rare thing, but I think you’re right. A lot is how it’s handled, and a lot is what’s developmentally appropriate. Maybe it’s fine for a kindergartner to have a one-to-one aid sitting next to them, but maybe in middle or high school, if a student needs aid assistance, it’s more often provided as in a more discreet manner by sort of a classroom aide who isn’t glued to one student. I think also sometimes when a student feels stigmatized and alienated by their special ed services, and as Ellen says, it may be because they find the services not helpful, or that the help, whatever helpfulness there is, is outweighed by the perceived stigma. And sometimes that’s an argument when the parents are seeking an out of district placement, for instance, at a specialized, either public or private, specialized program that only serves disabled students. Sometimes that’s an argument that the stigma is taking too big a toll on the on the student, and that they need a situation where they are throughout the day, or most of the day, with peers who share their needs. And I’ve certainly helped families get placements, whether it’s learning disabled students to go to a school for students with learning disabilities, that’s really the where I hear this the most, that the student who may have fought that placement all the way there, gets there and is so relieved that they are with other students who have dyslexia, let’s say, and that they aren’t the oddball. They’re now in the same boat with everyone, and they that can be really helpful for certain students. So, but, if the if the parent, if the parents perceive that there is a problem with stigma or with the services not seeming to be very useful to the student. I mean, that’s something again, to bring up in the first instance with the team or with the special ed administrator at the school. And if it can be addressed in that setting, maybe to think about other settings.

Gene 36:40

So, let me move to what more conceptual question. You know, current practice is that we see a lot of DEI or Diversity, Equity, Inclusion initiatives in schools, in the workplace, you know, in hospitals. And it occurred to us at the Clay Center after our last episode, that kids with medical and developmental disabilities are generally not part of DEI initiatives. So, I just you know, we may not have the answer to this. But what do you do? You think that would be useful Ellen and Eileen? I mean, or should we be rethinking how we look at DEI and this is a this is a substantial part of the population. And what about kids with chronic or, you know, medical or learning problems? Should they be part of DEI initiatives?

Ellen Braaten 37:41

I’ll let Eileen handle the legal part of that, but I can tell you that, and I’ll bring this up that, you know, I have a brother with Down syndrome, and I saw my mom, you know, he was one of the first kids after all, you know, like Public Law 94-142, that they said every child should have a, you know, an appropriate free education. I’m probably misspeaking this, but Eileen, you can correct me, but I saw my mom like, really, have to go to the school and say, like, you have to take my son that you can’t just leave him out just because he has a disability. And so, I’ve just always sort of thought that these kinds of issues are civil rights issue. Like it’s your right to be able to read, and so I do see these as part of that, that that it we don’t have equity in us in, you know, in some cases, for kids who need a different sort of way, you know, an adequate and equal opportunity. And so, you know, I do think that, but I have no idea if that’s a legally. If that’s correct.

Khadijah 38:51

Yeah, I think it goes back to the idea of stigma. And how do we make sure that we include kids with developmental disabilities and other challenges in the DEI initiative, so that they feel like they belong and that they are included in the community.

Gene 39:05

I think, frankly, they belong, not just in schools, but throughout DEI initiatives. I mean in hospital settings and workplaces. I mean, you know, DEI is an important, you know, movement, and there are DEI modules in most places now, but as far as I’ve seen, folks with developmental and medical problems are not generally included.

Ellen Braaten 39:32

And you know, this is sort of might seem like a random statistic, but there have been stats on our prison population that up to 70% of our prison population may have a learning disability and don’t have adequate reading skills. So, when we think about this, it’s really and then we think about sort of like the racial inequality in our in our prison systems, that this is an equity kind of issue. That being able to be a competent student has major, major consequences for society, for people to be able to live healthy lives and to achieve so this isn’t just about reading and, you know, writing okay and doing okay in school. It really has major consequences that are far beyond the school walls.

Eileen Hagerty 40:24

I would agree that disability should be part of any DEI initiative, just like race, gender, everything national origin, everything, everything else. And some students face more than one of those barriers to their education. As Ellen mentioned, the so-called school to prison pipeline where, you know, boys are more likely to be disciplined at school. Students of color are more likely to be disciplined at school, you know, than the students with disabilities that may or may not have been addressed properly, that give up and that end up in, as Helen says, in prison, or with other undesirable outcomes. So, I think, I think it’s also there’s a question of, how do you do DEI training with regard to disability that applies to all sorts of disabilities, because you can’t get too specific. I mean, a developmental disability is very different, different from, in many ways, from a learning disability, from an emotional disability. But I think a good trainer, and if any parent has the opportunity, if they know that a DEI trainer is going to be brought in, and if the parent has the opportunity to serve on some kind of advisory board, or even informally, to advocate for a trainer who knows about and can include disability in the DEI training, that would be, you know, that would be fantastic.

Khadijah 41:40

This has all been so great, and it’s about time for us to wrap up. But, before we do, what is one piece of advice that you think every parent should know before starting this type of process?

Ellen Braaten 41:53

I would say, Get informed. There are many, just like the clays, that are many ways to get informed and get educated, the more educated you can be as a parent, the better an advocate you can be for your child.

Eileen Hagerty 42:08

And I think one piece of information of advice that Ellen and I both gave at the end of the last program, so I’ll just allude to it briefly here, is when in doubt, get an evaluation, whether from the school or from an independent person. But we already said that. So let me just give one more piece of advice, which is the importance of the parents keeping their perspective. You’ve got to take the long view. This may be a long process. You’re going to be dealing with the school district as long as you have a child with a disability, and you live in the district. So, the importance of First of all, maintaining civility. You don’t have to be the best friend of everyone on the team. There can be conflicts that arise but keep it civil. That’s going to help you in the long run. And keep in mind your long view, or you’re playing the long game. It’s not a game, but you know what I mean. So don’t be discouraged by a team meeting that doesn’t go your way. There’s always something, almost always something else you can do, some other step you can take. And there are resources available to you to help, as Ellen said, Get informed. You can talk to a special ed attorney or advocate. You can talk to an evaluator, like Ellen and her staff. And there are many resources online and in books. I’ll just mention briefly two, if I might. The Wrights Law website, W, R, I, G, H, T, S, L, A, W, has a lot of information. And there’s a book by Pete and Pam Wright called From Emotions to Advocacy. And a less well-known book, but one that I think is very good also. It’s called Parents Have the Power to Make Special Education Work by Judith and Carson Graves, G, R, A, V, E, S, parents who went through the system themselves and then help others. And there are many, many others, you know, two to mention. But you can and their parents groups, as Ellen mentioned, Special Ed Council in your district, or just talking to others, you’ll find you’re a member of a club. You might not have initially thought you were going to be a member of when your child was born, but there are others out there who are interested.

[OUTRO MUSIC BEGINS]

Khadijah 44:12

We can’t thank you enough. Ellen and Eileen for joining us today for this special two parter. We’ve enjoyed having you on the show, and I think we have all learned so much.

Gene 44:21

And for those of you at home, if you’d like what you’ve heard today, consider leaving us a review. And as always, we hope that our conversation will help you have yours. I’m Gene Beresin

Khadijah 44:32

And I’m Khadijah Booth Watkins. We’ll see you next time you

[OUTRO MUSIC ENDS]

Episode music by Gene Beresin

Episode produced by Spenser Egnatz

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet