The Death Of Robin Williams: Two Psychiatrists’ Perspectives

Posted in: Hot Topics, Parenting Concerns

Topics: Hot Topics, Mental Illness + Psychiatric Disorders

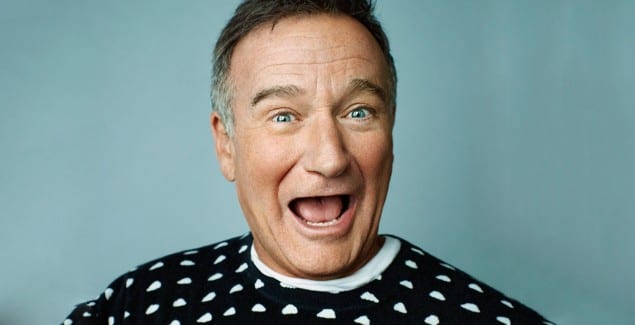

No one can deny that the untimely death of Robin Williams has affected us all in a multitude of different ways. In two separate blogs below, Drs. Schlozman and Beresin reflect on Mr. Williams’ legacy, what he meant—and still means—to them, and what we can all learn from this tragic loss.

***

Remembering Robin Williams:

Lessons On Depression From The Life Of A Beloved Celebrity

Steven Schlozman, M.D.

Robin Williams has died, and his passing makes me very sad.

I suppose that this sentiment goes without saying. I am, after all, not the only one who is sad, and there is certainly no way I am suffering more from his loss than others, countless others, who obviously knew him personally and thus also knew his joy as well as his anguish.

Still, I’ve tried over and over to begin this piece, and I can’t get beyond that first sentence. I’m so, so sad. Mr. Williams possessed the rare skill to make laughter and empathy intermix. In a world where humor itself so often derives from mean-spirited attacks and a desire to ridicule, Robin Williams managed to make you love, or at least respect, not only his characters, but also the antagonists to his characters. Look at Good Will Hunting, Patch Adams, Dead Poets Society, or even Mrs. Doubtfire.

It is also not lost on me that the movies I’ve listed, indeed a great many of his greatest roles, have psychological themes. Even Mork from Mork and Mindy was the consummate outsider. The pain of being alien became the laughter of discovery on that deceptively profound sitcom.

Among the many tragedies that stem from Mr. Williams’ suicide, it occurs to me that it’s a shame that he is not here to write his own commentary. I have an uncanny sense that he could accomplish what so many of us in the mental health community strive for but often miss. That is, he could help us all understand the pain of psychiatric suffering, and at the same time, the need for public empathy for these disorders. It is only through this combination that we will continue to make headway in the fight against these illnesses.

In fact, isn’t that what Robert De Niro’s character begs of Robin Williams when Mr. Williams plays Dr. Malcolm Sayer (Oliver Sacks in real life) in Awakenings?

“Learn!” he implores of the doctor. Learn from my suffering, in other words.

In honor, therefore, of everyone who has fought with a psychiatric illness, we owe it to each other to resist the urge to romanticize the suffering of these diseases, but at the same time, to maintain our empathy for those who suffer. These disorders are extremely common. Think of The Fisher King, another of Mr. Williams’ films with psychological overlay. As Parry, a professor who loses his wife in a tragic bar room murder, he becomes psychiatrically derailed and homeless. We have ignored or paid too little attention to these disorders for much longer than we can afford. And, we have not given those afflicted the kind of respect, and indeed admiration, they deserve—another powerful theme in the film.

There are many paradoxes we face when we attempt to comment on the suicide of a celebrity. We know that if we wax poetic too much, we run the risk of generating a narrative that paints the deceased as a romantically-struggling hero. This is not to say that Mr. Williams was not a hero, or by any means to suggest that he did not struggle. We must, however, be aware of the tightrope we walk as we write about these losses. There is clear evidence that any coverage that even appears to celebrate the lost struggle to suicidal urges runs the risk of glamorizing and sensationalizing the tragedy, thereby provoking further suicides. This is called the contagion or copycat effect, and it is well documented in the public health literature, particularly among adolescents and young adults. The CDC and American Foundation for the Prevention of Suicide even have guidelines for the coverage of suicide. We won’t belabor them in writing here, but you can click this link to learn more.

It would be silly, however, and even a bit disingenuous, to act as if the loss of a star as beloved as Robin Williams will not have ripples. As The Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds is devoted to fostering emotional well-being and resiliency, we feel it necessary that we address the means by which the ripples of this horrible loss can teach and inform us going forward.

What questions, then, have been asked most often with regard to this loss? What are my patients asking? What are their parents asking? What are my family and friends asking? Here’s a sample of what I’ve been continually asked for the last couple of weeks.

1. Is there an association between creative genius and psychiatric suffering?

This is, as one might guess, a controversial issue. There does seem to be a disproportionate number of celebrities, authors and artists who have suffered psychiatric disorders. In fact, some have noted that mood disorders and creative brilliance—in literature, music, graphic art, performing arts, even political leadership—are, in some ways, a packaged deal (see Touched with Fire, by Kay Redfield Jamison).

Some have even argued that this seemingly increased rate has lead to a kind of complacency amongst our most famous stars. These stars, some claim, are simply expected to suffer. Some might even be tempted to claim that, you must truly suffer pain to create art.

The problem with this argument is that celebrities with psychiatric suffering receive disproportionate media attention with regard to that suffering. The coverage of their struggle is greater, and the stories more carefully examined. Indeed, much of the worry about the suicide contagion effect that can follow celebrity suicides stems from the intense coverage that follows these kinds of events.

At the end of the day, the best message, it would seem, is that we all are at risk of developing these disorders. If we read more often about celebrities with psychiatric suffering, it’s because they are celebrities. They are, by definition, in the spotlight. Let’s not forget that the suffering exists well outside the circle of fame. And, let’s be very careful not to view this suffering as a kind of price one pays for genius. One can see very quickly how that message can be easily and dangerously misconstrued.

2. Why would someone as talented as Robin Williams take his own life?

This is, of course, a great and very complicated question. It’s not a great question because it’s perplexing; it’s a great question because it reminds us all that we are vulnerable to all sorts of diseases, and that these diseases sometimes win. Would the question be as potent if it concerned a different celebrity’s battle with cancer? Probably not, but it ought to be. Cancer, depression, substance use disorders…these are all diseases. They all have proven treatments, and we as a society need to remember that.

We also, however, need to remember that sometimes the disease wins. Whether the disease wins or not is not tied to talent or fortune; it is tied to the unique vulnerabilities of the individual and the disease from which he or she suffers.

We are all human, no matter how beautiful, rich or talented. We all have our histories, our vulnerabilities and our illnesses.

3. Did Mr. Williams fail to seek adequate treatment ?

Of course I can’t answer this question. I did not know Mr. Williams, and I also don’t know whether he received adequate treatment. What I do know is that the vast majority of people who do not seek help avoid assistance because of stigma. Psychiatric illnesses remain the black sheep of medicine. Patients with psychiatric diseases are still shunned in hospitals, avoided in the workplace, and even attacked by a separate number on the back of their insurance cards. It’s only through heightened awareness that we will win the battle against this prejudice.

Finally, and most importantly, don’t, not even for a second, shy away from Mr. Williams’ work. I still recall laughingly trying to drink with my finger when I first saw Mork and Mindy. That was just the beginning.

When I first heard of Mr. Williams’ death, I had an irresistible urge to watch The Fisher King. I also wanted to re-experience a less acclaimed film, Patch Adams, and see him again portray the tale of a man who combined medicine with humor and compassion to lighten the load on patients with serious illness. Interestingly, in this film, based in part on a real story, Patch Adams initially commits himself to a medical institution to find himself and his life’s work. He comes to appreciate that humor helps his fellow inpatients feel better. Thus, he embarks on medical school.

Mr. Williams was said to emulate the great improvisational genius, Jonathan Winters. Readers who are familiar with Mr. Winters’ work will know that he, too, fought his own psychiatric demons. Similarly, not for a moment does this fact take away from the joy he brought to others.

So, in closing, check out this clip of Mr. Winters and Mr. Williams together. The Internet is full of these memories.

And, for God’s sake, laugh! I didn’t know Robin Williams, but I’m fairly confident that he’d want us to continue to enjoy his work.

***

Staying Connected With Robin Williams:

How He Awakened The Ties That Bind Us

Gene Beresin, M.D.

Robin Williams is gone.

I, like many others, am shocked and sad. I feel like there is some kind of gaping hole, an empty space, maybe even a void. Something very important is missing from my life.

I don’t mean for this to sound selfish. Of course he is missing from other lives in ways that I cannot begin to understand. Nevertheless, I felt a kinship with Robin Williams that transcends my usual fondness for those who make a living by making others laugh. I suspect he would have made a wonderful shrink, though I am so glad he made his way toward the stage instead.

Those who knew him spoke of his kindness, his generosity, his brilliance, his creative genius, his warmth and, perhaps most of all, his sweetness. Many of these comments came from his dear friends, such as Henry Winkler, Jeff Bridges, Sally Field and others.

Others have written about the illness of depression—an illness that, despite treatment, may be fatal.

Some have focused on the issue of parity and the need for access to care, particularly for those with mood disorders.

Still, others have simply noted the tragic loss and mourned. We here at The Clay Center believed it necessary to note the stigma of mental illness, and the reluctance of so many to seek help as a result (see Steve’s piece on just that above).

But, we have not heard much about the reasons behind such a wide array of powerful reactions to Mr. Williams’ death. Sure, friends and colleagues who were close to Mr. Williams, who worked with and learned from him, have their very personal reasons.

But, how could such a death bring such powerful reactions to those who did not know him personally?

When I heard the news, I was in an Internet café in the Catskills. My daughter-in-law was searching the Web beside me, and suddenly burst into tears. “Robin Williams died. From asphyxiation.”

I was stunned. His image, in so many scenes, flashed hauntingly through my mind. As I said, I felt empty.

I was compelled to see him once again in some of my favorite films—just to be close to him: The Fisher King, Mrs. Doubtfire, Dead Poets Society, Good Will Hunting, Good Morning Vietnam, even Mork and Mindy or a random stand-up comedic performance.

We all have lost loved ones. We all have experienced the death of celebrities. But why did this death, obviously by suicide, create such a powerful reaction?

Robin Williams was a humorist, and he was a special kind of humorist. He combined making us laugh with making us feel what others are feeling, even his enemies. In other words, he skillfully enlisted our empathy. But how was it that we could immediately relate to him, and also feel for his opponents?

It seems to me that he had the uncanny ability to arouse laughter, pathos, rage and sympathy all at once. We walked in his shoes and in his opponents’ shoes at the same time. This was his magic, what made him compelling. It is also, by the way, the definition of empathy.

Robin Williams drew us into his world. He compelled us to live within his skin—within his humorous construct—to respond in a special way to and with him. That’s what makes him so special. He enabled us to laugh, to cry and to sometimes feel both simultaneously.

That quality is what made him special. That’s why we’re so sad. This experience of interpersonal communication is essential to being human. Rarely do we make such powerful connections with one another in everyday life, yet, we all need to feel connected—to laugh at ourselves, with and at others, and to even love the ones we hate. That is all part of our humanity. Robin Williams helped us experience those feelings. He enabled our engagement with others.

It is only when we are connected—attached emotionally to others—that we can really feel these things. We know when people are acting and when they are real.

Robin Williams was real to all of us.

And, given our connection with him and the experiences he stirred within us, we really have lost something—an enduring attachment figure—a parent, a spouse, a child, a friend.

Maybe he was trying to tell us in so many ways that we should all be searching for these very connections with each other in real-time.

Maybe he showed us how it could be done. And, sadly in our world, we lack some of this.

Thank you, Robin Williams.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet