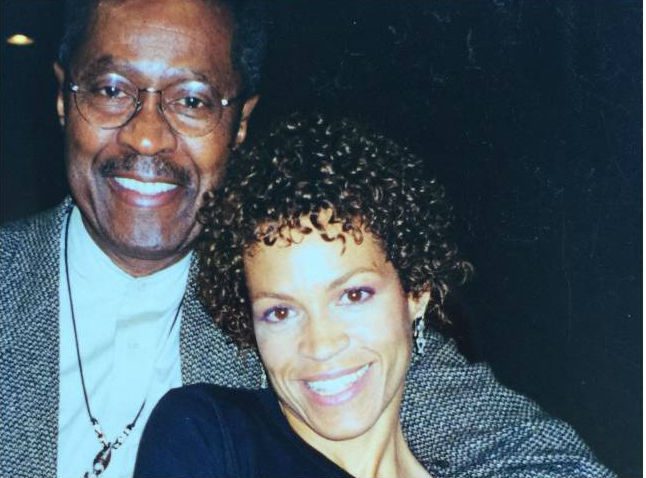

Dr. Chester Pierce: Reflections on my Treasured Mentor

Posted in: Parenting Concerns

Topics: Hot Topics, Real Lives Real Stories

Center for the History of Medicine (Countway Library) (repository) and Perspectives of Change: The Story of Civil Rights, Diversity, Inclusion, and Access to Education at HMS and HSDM, “Oral history and a transcript for an interview with Chester Pierce, Perspectives of Change,” OnView: Digital Collections & Exhibits, accessed February 23, 2023.

I came to Massachusetts General Hospital in 1978 as a first-year psychiatry resident. My goal was to be a child and adolescent psychiatrist, and a clinical educator. From the outset, my program director, Jon Borus, and Chief, Tom Hackett, said that I would benefit from getting to know Dr. Chester Pierce, who was on our faculty, and a professor in the Harvard Graduate School of Education. I was initially intimidated reading a bit about his career.

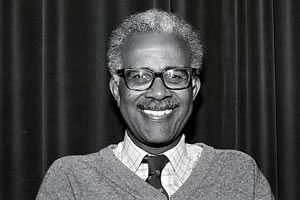

Chet graduated from Harvard College and Harvard Medical School. His career was absolutely stellar: A Commander in the United States Navy; a Harvard College athlete, and the first African American to play a college football game below the Mason Dixon line against the all-white segregated University of Virginia; an expert in research in many arenas, including studying isolation of astronauts for NASA in the Antarctica because of the need to put some people in stressful situations in preparation for a 3 year crew for a mission to Mars (and having a mountain named after him – Pierce Peak); President of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology; elected to the National Academy of Sciences; and had a research seminar in his name awarded by the American Medical Association. He was a dedicated to studying the impact of social inequities, culture, and racism on mental health, and was the first to coin the term “microaggressions.” In the MGH Department of Psychiatry he focused on international mental health, and we now have our Division of Global Psychiatry named after him. He was a senior consultant to Sesame Street, which in particular appealed to me as a future child psychiatrist. I could go on with innumerable awards, national and international positions of leadership. No doubt I was intimidated!

I distinctly remember our first meeting. We went to lunch in the MGH cafeteria. I had never seen him before, and there he was – a very tall, slender, and distinguished looking man, who truly stood out in the crowd. He approached me, and reached out to shake my hand, and said what a pleasure it was to meet me, see me in person, and how many wonderful things he heard about me. He knew my aspirations, my interest in kids and healthy development, my activism in college (for civil rights, working for the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee), and my interests in music. He said he was so impressed, he wanted to hear about me. And we talked. He quietly took everything in. I felt seen and heard.

Chet was nothing that I expected. He was soft-spoken, curious, and above all humble. Not a word was spoken about himself, his vast achievements, or what he could do for me. He was hopeful that I could do something to help him learn. Learn? About what? Who was I, this lowly inexperienced beginner going to teach this grand professor? But that was the heart and soul of Chet. His humility, his love of learning, his gratitude for an ability to interact and develop a relationship were at the core of his being. He was a quiet man – one who listened, who did not dominate the conversation, who paused at length between his frequent, though sparse, pearls of wisdom. He was as kind and gracious as they come. I knew I could learn so much from him. And I did.

When I came on the faculty, we had many conversations about supporting underserved minorities. He inspired me to take on the Elizabeth Thatcher Acampora Endowment for Underserved Children and Families in the Community – an endowment in Chelsea, Revere and Charlestown that still is running to this day. He was a seminal part of our General Psychiatry Admissions Committee. He would often sit in a comfy chair behind the grand conference room table in the Hackett Room. And he would rarely say anything, but when he did, you could hear a pin drop. I recall as we were so often geared up to recruit residents from underserved populations, if the candidate had weaknesses or was not up to par with our other residents, he would not allow color, race or minority status to cloud his judgement that the fit was not right. He wanted to produce the best psychiatrists we could, and he quietly made his assessments known.

Finally, we spent many talks considering the importance of resilience in child and adolescent development. I have long been an advocate in promoting resilience in young people. Chet, from his personal and professional experience in the wilderness, as a commander, playing football during segregation amidst jeers and howls, and in his work in global health was succinct, and right to the point. He said: “Gene, you know kids are not born resilient. No one is. It’s a process you learn, not a trait. Resilience is a double-edged sword – one edge prevents adversity, the other provides coping mechanisms during hard times.” And the more I read the research on resiliency, it was clear that Chet captured the essence of this process so elegantly, brilliantly, and succinctly.

We also talked about the African diaspora, about systemic racism, particularly in healthcare and in universities, including at Harvard. He organized an “African Diaspora” conference in 2002 to bring together psychiatrists from all over the world to discuss issues and problems. This conference was convened only after he had partially retired, sharing the dream to create such a meeting. The department immediately raised funds to support the mission. Characteristically, the last night of the conference when our Global Mental Health Division was going to be named after him, he did not show up. My colleague John Herman jokingly diagnosed him with “pathological humility.”

Chet would write thank you notes on white notepaper clearly purchased at the five and dime store. John said that his stationary had none of his superlative titles. So, he gave Chet a gift of personal stationery on Harvard letterhead with all his titles. John received a thank you note on white notepaper. Chet never used the stationery.

In all of our talks, no matter how painful the subject matter, particularly about inequities, racism, and social injustice, Chet never got angry. He remained calm, collected, thoughtful, and gentle in every way. He had a wonderful sense of humor, a great respect for differences of opinion that he heard without condemnation or judgement.

I think of Chet often. He is the kind of doctor, professor, mentor, indeed, the kind of human being I treasure.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet