Dad’s New Shoes

Posted in: Hot Topics, Podcast, You & Your Family

Topics: Relationships

Intro and outro music written and performed by Dr. Gene Beresin.

Today’s dads are confused.

It might not be a bad kind of confusion, but confusion is still the best word for how dads feel. If we pretend that the role of the modern father is clear-cut and obvious, we’d of course be acting a bit disingenuous.

Times have changed. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, for example, the so-called “nuclear family” was the ideal. At least that’s what was depicted on TV. Or there were those who were divorced, kids living most of the time with Mom. In that scenario, dads were largely “weekend fathers.” But over the last three decades, there has been a dramatic shift in family structure, and consequently, the roles of dads.

We now have two-father families, single fathers, stay-at-home fathers, fathers who work part-time, and so on and so forth. Literally. We could go on (with so on’s and so forth’s) for an entire post just delineating the various ways dads are dads in this quickly-changing culture.

And, as often happens when ideas are in flux, these changes come with a bit of hand-wringing. In 2011, author Ray Williams wrote an influential post where he decried “The Decline of Fatherhood.”

Last year, Michael Winrip wrote an editorial in The New York Times noting that as a dad, he “wants it all.” He stresses that he wants to be with his kids, that he craves kudos at work, and that he wants these accolades in equal parts. In what some have called the-mirror-image-of-what-moms-faced-in-the-past-three-decades, dads are toying with their roles as never before.

And that can be confusing for everyone.

But are these changes really that new? Maybe it’s just that I’ve been around so long, that I’ve seen so many different perspectives, that I am finally realizing that there are just no clear answers.

Still, these sentiments beg an important question. What is the work of fatherhood in 2014? And, how do dads do it well?

There are, of course, some basic facts propelling these cultural shifts. Many families, perhaps even most, need two incomes. Women continue to emerge and strengthen their presence in the workforce. In fact, according to The Pew Research Trust, women are the primary wage earner in about 40% of American families. Some of these numbers refer to single parents, while many others describe situations with fathers at home, often sharing or taking primary responsibility for the kids. The “stay-at-home dad,” previously an anomaly, is becoming an accepted role. Certainly, there’s no shortage of TV shows that have men cast in this role. We have come a long way from Leave It To Beaver.

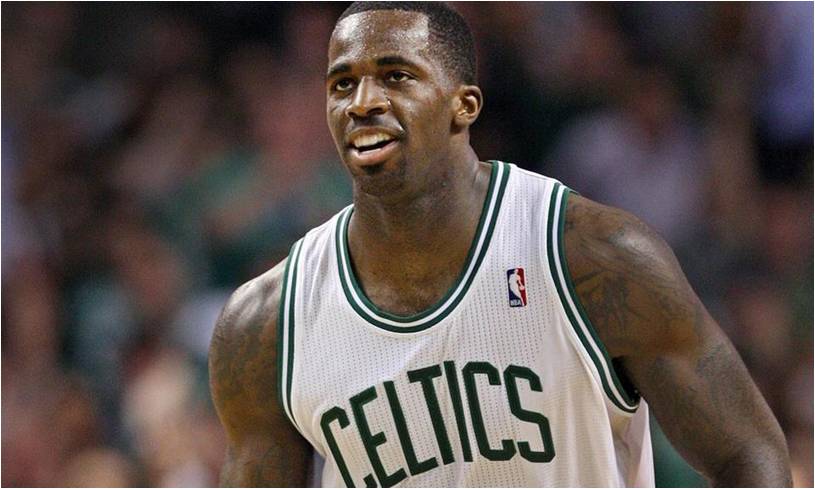

Male professional athletes are regularly tearful on TV. When they celebrate victory, they often have a young child on their lap. In today’s world, fathers can be emotional and still remain examples of masculinity in all walks of life.

What does this trend mean for fatherhood? Is it a wholesale change in the conceptualization of being a dad, or are these evolutionary steps that were always present, but can now be shown with increased and welcomed acceptance?

In addition to being providers, and at times, protectors, we fathers are now asked to also be both emotionally vulnerable and emotionally engaged with our children. We welcome the opportunity to celebrate our interest and enthusiasm with regard to what our children feel, and when they feel it. We are asked to accept and support all of their emotions without judgment, exhibiting understanding and curiosity. And in this role, we certainly need to know their friends, their interests, their fears, their weaknesses and their talents. We need to be able to reveal our own emotions to them directly.

Moreover, is all this change necessary? Is it good for our culture?

Absolutely!

We have very good data that children fare better socially, emotionally, behaviorally and academically when fathers are emotionally engaged. We know that optimal brain development occurs with more engaged dads. We know that today’s fathers must be attuned, empathic, understanding and willing to correct miscommunications and failures. Perhaps some of the hand-wringing stems from the fact that these changes have come about in a relatively short period of time. For generations, fathers were largely distant, quiet and disciplinary.

Not anymore.

While mothers continue to have a special place in the lives of children, we fathers are increasingly asked to have our own ways of feeling close to our children.

We can engage in physical play, we can read together, we can talk together, we can cook together—it’s the emotional engagement and involvement that matters. Often, having fun with your child is the best indicator that all is well. But research shows that it’s not just the fun times together that foster a close, warm relationship. Rather, it’s the daily mundane tasks—from changing diapers and potty training, to putting kids to bed, to shopping for meals and school supplies—that predict healthy, secure attachment and sound adjustment among children.

Don’t misunderstand. John Wayne movies are still fun. But, the stereotypic roles of Mr. Wayne’s characters (the strong, silent and unemotional type) are waning. Life has become more complex.

Being an emotionally-engaged father is good for our children, and good for us. That’s an enormous change from a few generations ago.

Like any skill or job well done, being a good father makes us feel better about ourselves.

In Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, a cohort of soldiers has the assignment of bringing another soldier, James Ryan, safely home to his mother. Private Ryan’s mother has already lost three sons to the war. The men are determined to prevent a fourth death. Fifty years later, civilian Ryan wonders whether he has lived a life worthy of having been saved at the cost of other soldiers’ lives. With his children and grandchildren behind him, James Ryan says to his wife, “Tell me I have lived a good life. Tell me I am a good man.”

In other words, tell me that I’ve been a good father.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet