How to Understand Your Child’s “Anxiety Monster”

Posted in: Parenting Concerns, Stress

Topics: Anxiety, Mental Illness + Psychiatric Disorders

As a child psychiatrist who’s seen patients in many different settings, including doing psychotherapy and managing medications, I’ve found that talking about anxiety with kids and adults alike is hard to do in a way that helps them understand what anxiety is, while preparing and motivating them for what can be a difficult treatment journey. There’s a lot of information out there about the treatment of anxiety, which often involves exposure-based therapy with principles derived from Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

So, instead of talking about traditional treatment, I want to offer a metaphor I’ve found helpful for describing anxiety to child patients and their parents. I started using this metaphor when I was working with young children, but over time I started using it with all patients, including adults. Simply, I explain that anxiety is like a small monster that sits on their shoulder and whispers in their ear.

The Anxiety Monster tries to convince people that if they attempt to do something:

- Something bad will happen.

- This bad something will have REALLY bad consequences.

It’s important to remember that anxiety exists on a spectrum, and can even be helpful at times if we can focus the energy to plan for events like tests or meetings. But sometimes anxiety can exist in a more insidious form and negatively affect our lives – for example, as an actual disorder.

While the Anxiety Monster is whispering in people’s ears, I describe that it also pokes them and causes a discomfort that is hard to describe, though we’re all familiar with it. We’ve all had our versions of anxious thoughts, and at times this discomfort comes with them. For some, it can feel like a pit in their stomach. For others, it includes faster and more shallow breaths, feeling their heart rate increase, or possibly even feeling sick to their stomach.

The Anxiety Monster on a person’s shoulder says that instead of doing a particular thing, they should avoid doing it.

For example, the Anxiety Monster whispers:

“If you take the shot, you’ll miss—so don’t take it…”

Or:

“If you ask her out, she’ll say no—so don’t bother…”

Not only that, but it magnifies the perceived consequences of what someone thinks will go wrong:

“…AND if you miss that shot, no one on your team will like you.”

“…AND if she says no, it’s because no one would want to date you.”

The Anxiety Monster persuades people to avoid activities in daily life by saying bad things will happen if they act, magnifying the perceived consequences of failure, and also by promising to stop poking them (take away the uncomfortable feeling) if they avoid the situation. If they avoid, the monster gives them temporary relief from that horrible feeling and worrying thoughts.

This is a key point of treatment for anxiety. Avoidance feeds anxiety.

I conceptualize the Anxiety Monster as a creature whose sole purpose it is to continue its own existence, like a parasite. When patients avoid doing something that makes them anxious in order to seek temporary relief, I describe that they actually feed the Anxiety Monster a little cookie, making it a little larger, its pokes a little stronger and more uncomfortable, and its whispers a little louder and more convincing in their ear the next time.

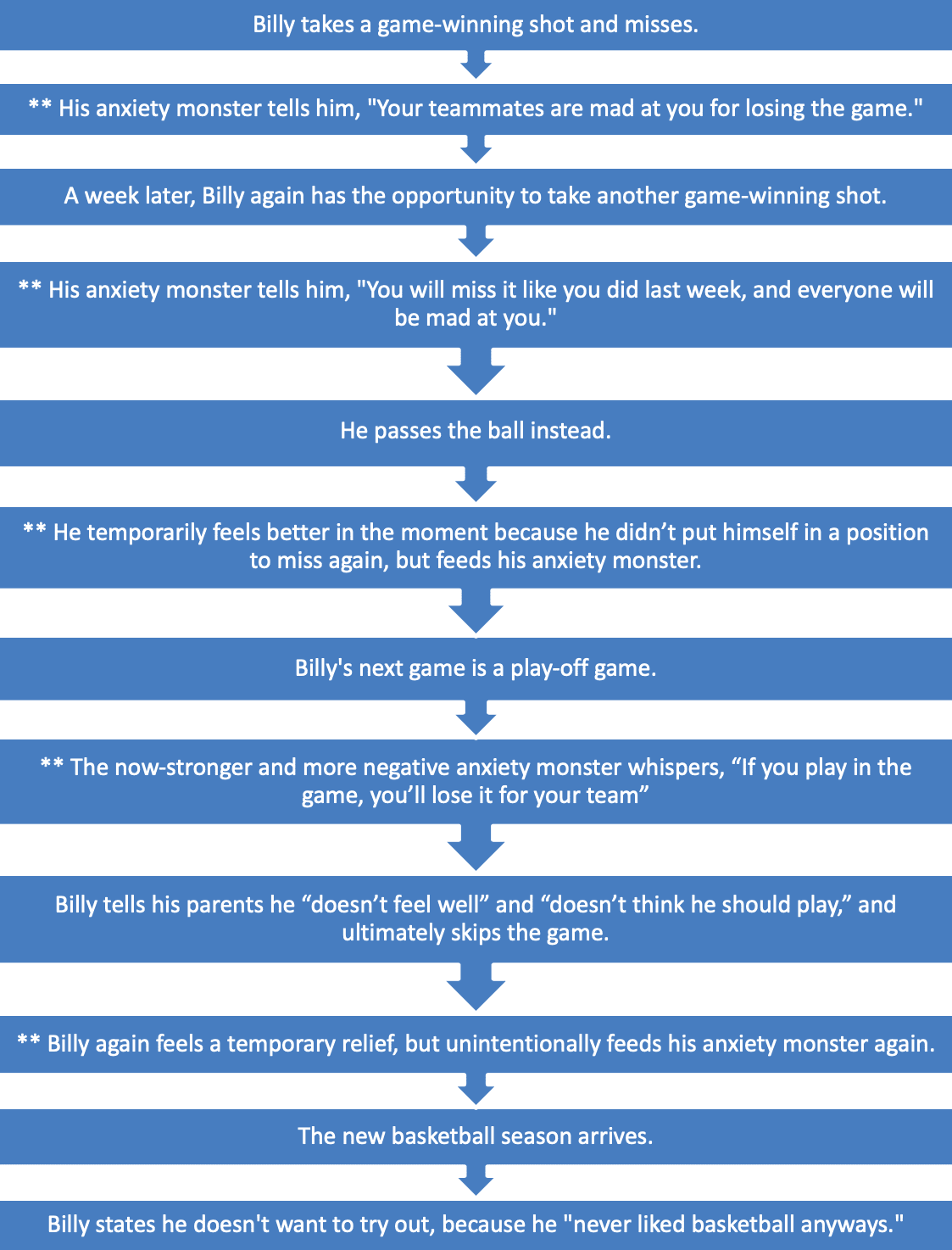

When someone starts to avoid activities more than they confront them, they can get into an avoidance spiral, where they start to lose control over their Anxiety Monster. Follow how our basketball player, who we’ll name Billy, has more and more avoidances due to his growing Anxiety Monster (anxiety monster influences noted with a *).

In this case, it’s not actually that Billy didn’t enjoy basketball, but that the discomfort and negative thoughts caused by his growing Anxiety Monster grew with each new avoidance—not taking a shot, skipping a game, and ultimately not trying out next season. The discomfort eventually outweighed the enjoyment he used to get from playing the game.

Through this process, kids and teens can lose the enjoyment of sports, school, and even spending time with family and friends.

Now, you may ask yourself, “Aside from having a cutesy description of anxiety, why is this metaphor helpful?”

In addition to allowing us to think about how anxiety acts and grows through avoidance, this metaphor also helps us to externalize the actions of anxiety. In an overly simple sense, anxiety works by “distorting” thoughts towards the negative to keep people from doing the things that help fight or manage anxiety. When the Anxiety Monster whispers in people’s ears for a long time—sometimes years—it’s common for them to start thinking of the Anxiety Monster’s whispers as their own thoughts, which leaves them unable to challenge them, as is required with the treatment of anxiety.

So, to help separate an anxiety disorder from my patient’s thoughts, I will name the metaphorical Anxiety Monster to help them further externalize anxiety from themselves, making it easier for them to challenge the anxiety with exposures and other CBT tools. With older kids and adults, I often will recommend the name of Petyr Baelish, or “Little Finger,” from Game of Thrones. If you remember, he was a character that was present throughout most of the show and was charming, manipulative, and convinced people that they were doing the right thing by doing what he wanted. All the while, he got his needs met and ultimately sacrificed those people for his own gains. Sound anything like our Anxiety Monster?

Once people better understand how anxiety acts on them, and start to externalize anxiety from their own thoughts, it gives them the ability to take the next necessary steps of challenging their Anxiety Monster with proven therapies, including CBT principles such as exposure. Just like avoidance feeds the Anxiety Monster, exposure and doing the things that are important to a person starve it, stripping the monster of its power and persuasion.

By externalizing anxiety thoughts from themselves, people can trust that when they feel uncomfortable during therapy, they are actually working to lessen anxiety, as opposed to thinking that the uncomfortable feeling is the same as doing something “bad” or “wrong.” It changes the whole frame of the treatment and how people think, with patients starting a new cycle of getting their life back, reclaiming control of their thoughts, and regaining values and goals that were previously lost to the soon-to-be powerless Anxiety Monster.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet