What if My Child has Oppositional Defiant Disorder?

Posted in: Parenting Concerns

Topics: Behavioral Issues, Mental Illness + Psychiatric Disorders

The first time I met Jacob’s mother, she came into my office in tears.

“You won’t like my son,” she said. “He is in the car in the parking lot and refusing to come in to see you, but this is nothing new. Yesterday he wouldn’t get dressed so I took him to Kindergarten in his pajamas thinking that once we pulled up to the school he’d hurry up and get dressed. But that didn’t faze him at all. He just sat there and refused to get out of the car.”

When I asked her about a “typical” day for Jacob, she replied:

“A typical day is one where he gets up on the wrong side of bed. He doesn’t like the cereal we have and won’t get ready for school. He annoys his sister all day long and blames her when he gets in trouble. He can argue with me about anything – his shirt is too ‘itchy,’ or he doesn’t want to wear a coat even when it’s freezing outside.”

Jacob’s mother was clearly at her wit’s end and was coming for assistance to see how she could help Jacob get control of his behavior.

I met with Jacob and, although he was in many ways a very adorable 5-year-old, he was frequently argumentative and irritable, especially to his mom. He was often touchy and easily annoyed. After a thorough evaluation, I diagnosed him with Oppositional Defiant Disorder.

What is Oppositional Defiance Disorder (ODD)?

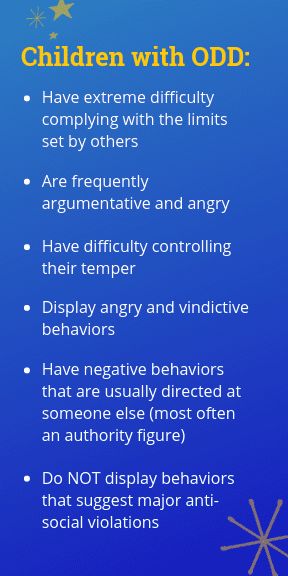

Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) display patterns of behaviors that include negativity, hostility, and defiance that are above and beyond what is expected for a child of that age.

Children with ODD frequently argue with adults, lose their temper, are often angry and resentful, do not comply with adult rules, annoy others, and blame others for their problems. These behaviors are almost always present at home and sometimes at school and in other settings. ODD is more common in boys than in girls before puberty, but equally common after puberty. Symptoms are typically present by eight years old. It is important to remember that these symptoms need to be severe enough to interfere with a child’s day-to-day functioning. Most adolescents display some of these behaviors at one time or another, but they would not necessarily meet criteria for this disorder.

Typically, children with ODD save their worst behaviors for those they know well. It can be a difficult disorder to diagnose because these children don’t always show symptoms in the psychologist’s office. When asked why they act the way they do, they often blame their parents, teachers, or other adults for their issues. It’s common to hear adolescents with ODD say things like, “If my parents weren’t so strict, I wouldn’t be acting this way.” Sometimes these children can be so convincing that the psychologist or teacher believes that the parent really is the problem! This is seldom the case.

ODD typically begins before age eight and rarely begins later than early adolescence. Quite often parents will report a long-standing history of temper tantrums, moodiness, and low frustration tolerance. These children are often described as having a “difficult temperament,” and it’s true that some children with difficult temperaments do grow up to have ODD – particularly if they are a poor match for their family environment. In other words, a child who might have been described as a “spirited” child, but who was born into a quiet, placid family might not “fit in” with the family’s dynamics and, thus, the parents may have difficulty understanding their child or making the necessary adjustments (within the family system) to that child’s temperament.

Frequently, ADHD is present with ODD, but not always. Sometimes children with preexisting depression or mood disorders can display these behaviors, and if that is the case, the mood disorder is considered the primary diagnosis. Often, when the depression is treated the oppositional behaviors go away. Overall, children with ODD tend to have higher rates of co-morbid disorders, social impairments, and family dysfunction.

How is ODD Assessed?

When a diagnosis of ODD is suspected, the psychologist will initially want to conduct a thorough assessment looking at the child’s developmental history (including milestones, medical history, family history), and school history (including how the child’s behaviors impacts him or her in the classroom).

It is important for the psychologist to clearly assess the situations and environmental triggers that can be contributing to the child’s oppositional behaviors. Do these behaviors only occur at home, at school, or during unsupervised play times? Are there certain people in the child’s environment with whom he is more likely to exhibit these behaviors? For instance, are the behaviors worse with dad, mom, teachers, coaches, or peers? Are there certain types of situations that can trigger these behaviors?

Because there are many factors that can contribute to a child’s acting-out behaviors, it’s not usual for the psychologist to request further testing, such as psychological testing or neuropsychological testing. Further testing can be useful in determining the child’s:

- cognitive and emotional strengths and weaknesses;

- development (or lack thereof) of executive functions skills such as planning, organization and flexibility;

- language skills;

- social skills;

- problem-solving skills.

For example, Jacob was referred for a full neuropsychological evaluation. The results of the evaluation indicated that he had a Nonverbal Learning Disability which may make him prone to difficulties interpreting nonverbal cues in the environment and transitioning from one activity to another. He also displayed difficulties with working memory skills in that he had difficulty remembering what he was supposed to be doing. When Jacob’s mother asked him to go up to his room, get his white socks and blue sneakers, and bring them downstairs, it was too much information for him to remember. He wasn’t necessarily being defiant when he came down from his room without his socks – he really couldn’t remember all of the information he was asked to remember.

Through this evaluation, Jacob’s parents gained a better understanding of the factors that contributed to his oppositional behavior and his therapist could use this information to guide her treatment.

While most children with ODD do not meet criteria for a Nonverbal Learning Disability, many do a display a particular cognitive style that makes them prone to oppositional behaviors. Researchers, such as Kenneth Dodge, have found that aggressive children tend to have deficient information processing skills regarding social situations – they misperceive social situations in particular ways, by misinterpreting or under-using social cues in the environment. They misattribute hostile intent to their peers. On problem-solving tasks, they tend to generate fewer solutions to problems. Surprisingly, they expect to be rewarded (not punished) for aggressive behaviors. This style makes them prone to making bad decisions because they’ve misinterpreted what’s gone on in the environment, or not making the right decision because they never generated enough ways to solve the problem. Acting aggressively might have been the only solution they thought of – and at the same time they might think their solution “solved” the problem and they expect to be rewarded for their efforts.

How is ODD Treated?

Many different types of treatment have been used to address children’s ODD behaviors.

Some programs have focused on changing the discipline techniques of the parents that have contributed to the development of oppositional behavior and poor parent-child interactions. These programs teach skills such as use of time-outs, use of appropriate language, and how to use reinforcement.

Other programs have focused on the cognitive factors underling the child’s behaviors. The Collaborative Problem-Solving approach, at Think:Kids, is an example of one of these types of programs. This approach:

- Helps the parents understand the parent and child characteristics that contributed to the development of the oppositional behaviors;

- Makes parents aware of the strategies for handling unmet needs or expectations (for example, parents can impose their “will” collaboratively problem-solve with the child; or remove the expectation that the child behaves in a different way);

- Helps parents understand how each one of these strategies impacts parent-child interactions;

- Helps parents learn how to use collaborative problem-solving as a way to resolve disagreements and oppositionality.

Recent research over the past decade has shown this model to be quite effective.

It’s important to keep in mind that children with ODD can vary considerably and there is no “one size fits all” approach. A child whose problems are fueled by poor language comprehension is going to need a different approach from a child whose problems are fueled by a co-existing depression. Thus, it’s important to work with a psychologist who has expertise in working with these children so that they can individualize the treatment based on your child’s needs at that particular time.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet